Table of Contents

Historic trends in ship size

Published 22 December, 2019; last updated 3 October, 2022

Trends for ship tonnage (builder’s old measurement) and ship displacement for Royal Navy first rate line-of-battle ships saw eleven and six discontinuities of between ten and one hundred years respectively during the period 1637-1876, if progress is treated as linear or exponential as usual. There is a hyperbolic extrapolation of progress such that neither measurement sees any discontinuities of more than ten years.

We do not have long term data for ship size in general, however the SS Great Eastern seems to have represented around 400 years of discontinuity in both tonnage (BOM) and displacement if we use Royal Navy ship of the line size as a proxy, and exponential progress is expected, or 11 or 13 in the hyperbolic trend. This discontinuity appears to have been the result of some combination of technological innovation and poor financial decisions.

Details

This case study is part of AI Impacts’ discontinuous progress investigation.

Background

According to Wikipedia, naval tactics in the age of sail rewarded larger ships, because larger ships were harder to sink and could carry more guns, and battles were usually lengthy affairs in which two lines of ships fired at each other until one side surrendered.1 2 Our understanding is that when steamships and iron-clad ships appeared, financial constraints sometimes prevented navies from building as large as technically possible, but the incentives towards bigger ships remained, since the best way to punch through heavy armor was to carry heavy guns, which required a big ship.3

Trends

Royal Navy first-rate line-of-battle ships ‘tonnage’ (BOM)

‘Tonnage’ (BOM) is a pre-20th century measure of ship cargo capacity.5 It is calculated as:

We use it because that’s what we have data on; displacement, the modern way of calculating ship weight, was not widely recorded until towards the end of our dataset. Unfortunately, BOM seems to be less accurate for estimating the cargo capacity of ships after 1860, which could affect our findings in this report. However, our Spot check section offers some evidence that this choice of metric isn't responsible for producing the largest discontinuity as an uninteresting artifact.

Data

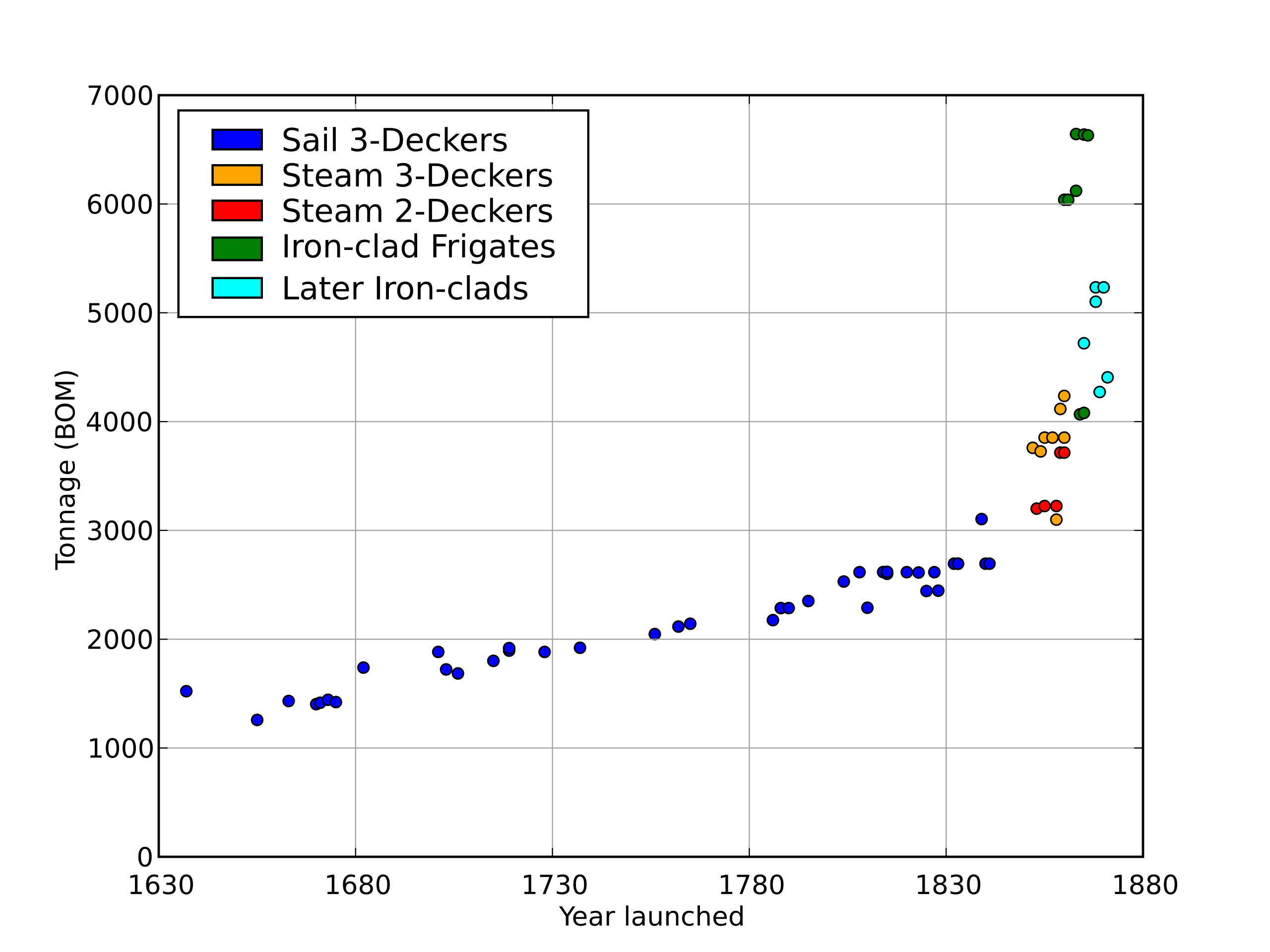

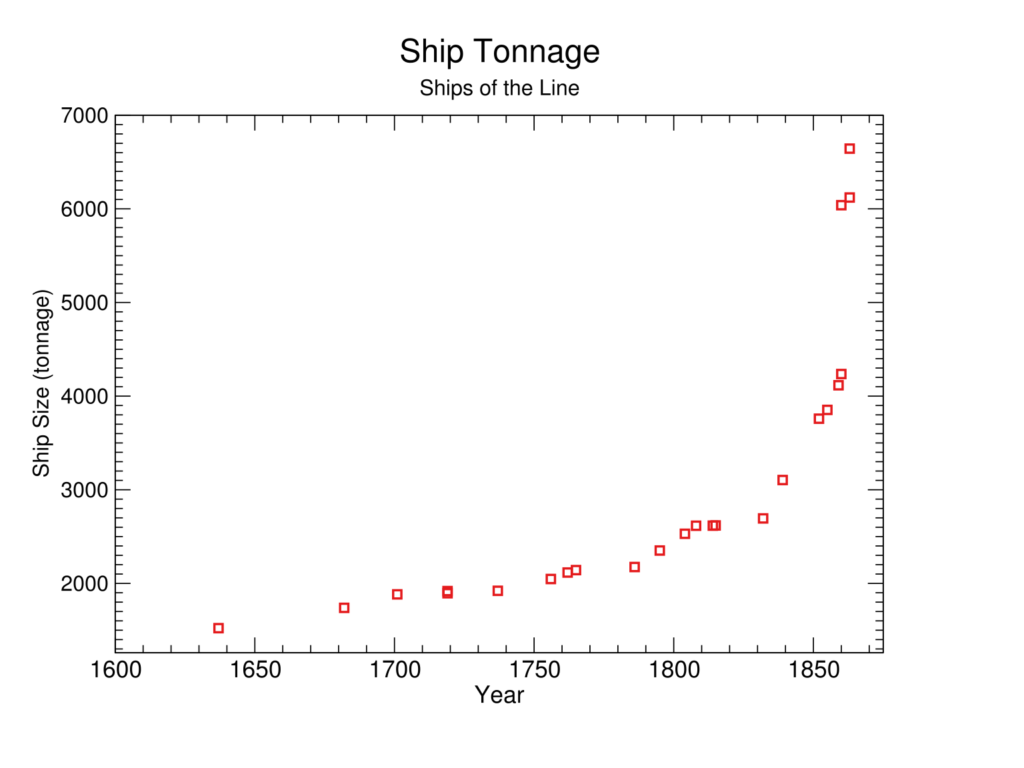

Figure 2 shows ship ‘tonnage’ (BOM) over time for UK Royal Navy first-rate line-of-battle ships, according to Wikipedia contributors Toddy1 and Morn The Gorn.6 This spreadsheet contains their data. We have not vetted it thoroughly, but have spot-checked it (see Spot check section below). We extract the record-breaking subset of ships (see Figure 3).

Discontinuity measurement

Exponential prior

If we have a strong prior on technological trends being linear or exponential, we might treat this data as a linear trend through 1804 followed by an exponential trend.8 Extrapolated in this way, tonnage saw ten greater than ten year discontinuities in this data, shown in the table below.9

| Year | Tonnage (BOM) | Discontinuity | Name |

| 1701 | 1,883 | 11 years | Royal Sovereign |

| 1756 | 2,047 | 13 years | Royal George |

| 1762 | 2,116 | 10 years | Brittania |

| 1795 | 2,351 | 31 years | Ville de Paris |

| 1804 | 2,530 | 25 years | Hibernia |

| 1839 | 3,104 | 41 years | Queen |

| 1852 | 3,759 | 41 years | Duke of Wellington |

| 1859 | 4,116 | 12 years | Victoria |

| 1860 | 6,039 | 77 years | Warrior |

| 1863 | 6,643 | 13 years | Minotaur |

| 1867 | 8,946 | 33 years | Inflexible |

In addition to the size of these discontinuity in years, we have tabulated a number of other potentially relevant metrics here.10

Other curves

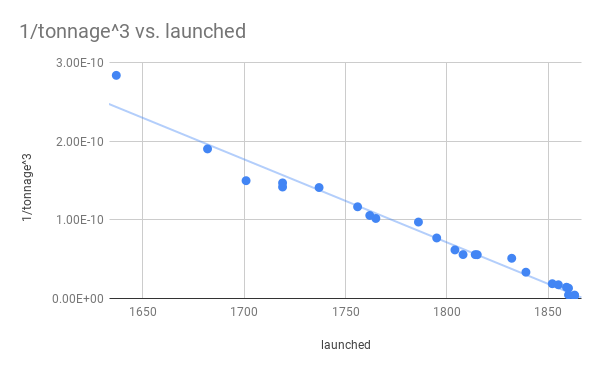

With a weaker prior on linear or exponential trends in technology progress, one might prefer to extrapolate this data as a more exotic curve, such as a hyperbola. For instance, Tonnage = (1/(c*year + d))^(1/3) for some constants c and d appears to be a good model, since 1/(tonnage^3) looks fairly linear (see Figure 4).

Using this to extrapolate past progress, we get no discontinuities (see our spreadsheet, sheet ‘Tonnage calculations’ for this calculation). However this is unsurprising toward the end, since hyperbolas have asymptotes (potentially going to infinity in finite time), and this particular one reaches such a singularity in about 1869. So on that model, any size ship is expected by 1869, and discontinuities cannot be larger than the time remaining until that date. (The largest discontinuity is nine years, from Warrior, which is within a year of the implied ship-tonnage singularity.)

Discussion of causes

Given that modeling the data as hyperbolic means there are no discontinuities, a plausible cause for apparent discontinuities when modeling it as exponential is that the process of ship size increase is fundamentally closer to being hyperbolic (though it must have departed from this trend before long, since it would have implied arbitrarily large ships from 1869). We do not know why this trend in particular would be hyperbolic, given that we understand exponential curves to be much more common in technological progress.

On a brief investigation of possible causes of particular discontinuities in this trend, Ville de Paris, Hibernia, and Queen do not appear to use any dramatically different technology to previous ships.

The Duke of Wellington was the first Royal Navy ship of the line to be steam powered, and it was apparently lengthened to fit the engines.11

The largest discontinuity was from Warrior, which was one of the two first armor-plated, iron-hulled warships.12 It seems likely that iron hulls allowed larger ships. For example, the wooden steamship Mersey, unusually large for a wooden ship yet smaller than the Warrior, is considered to have been beyond the limits of wood as a structural material.13 Moreover, the very large civilian ship Great Eastern, made extensive use of iron for structure and appears to have been regarded as innovative for its structure.14 So plausibly this was an important enough innovation to produce an immediate jump in ship size.

Spot check

Our metric, BOM, doesn’t measure volume or weight directly; it is derived from a ship’s width and length. Thus it might often be a reasonable proxy for a more normal notion of size, but change arbitrarily between different ship designs. There is particular reason to suspect this here, since according to Wikipedia, “[s]teamships required a different method of estimating tonnage, because the ratio of length to beam was larger and a significant volume of internal space was used for boilers and machinery.”15

To check whether the Warrior discontinuity was an artifact of this measurement scheme, we also searched for displacement figures for some of these ships. (We also made a brief attempt to find ships from other navies, like the French, that might destroy the discontinuity. We didn’t find any.) We did not collect many, but they cover the period of the largest discontinuity, 1850-1860, and confirm that it is probably robust to different ship size metrics, and thus not an artifact. See this spreadsheet.

Royal Navy first-rate line-of-battle ships displacement (tons)

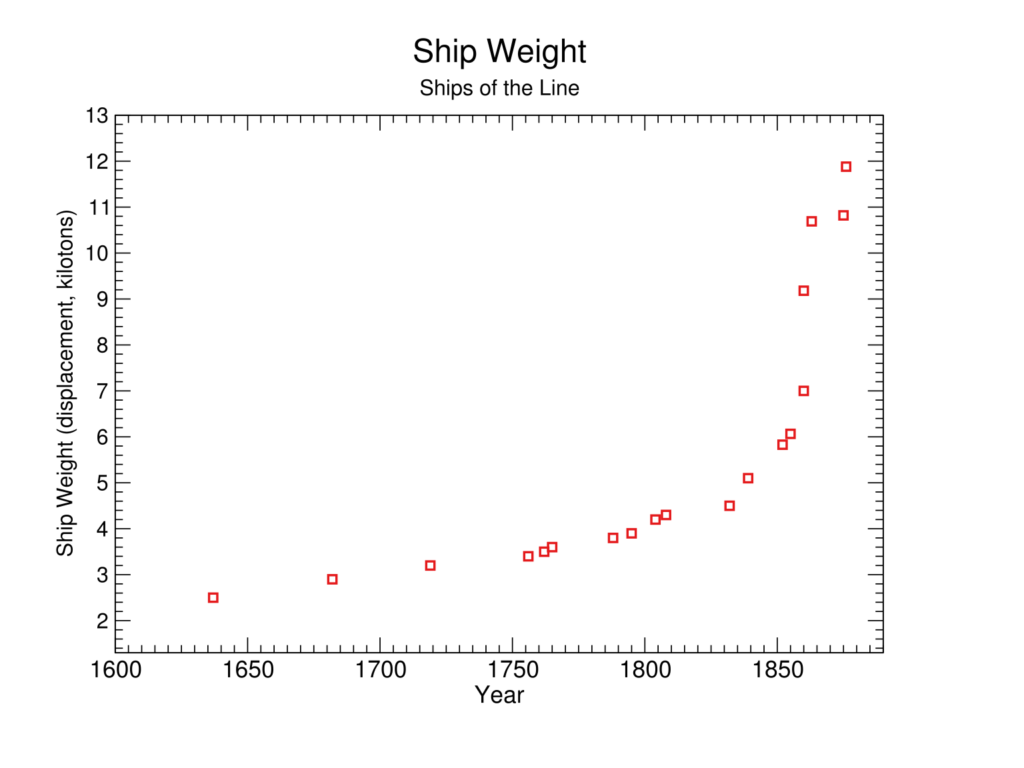

The displacement of a ship is its weight, measured by looking at the amount of water that a ship displaces when it’s floating.16

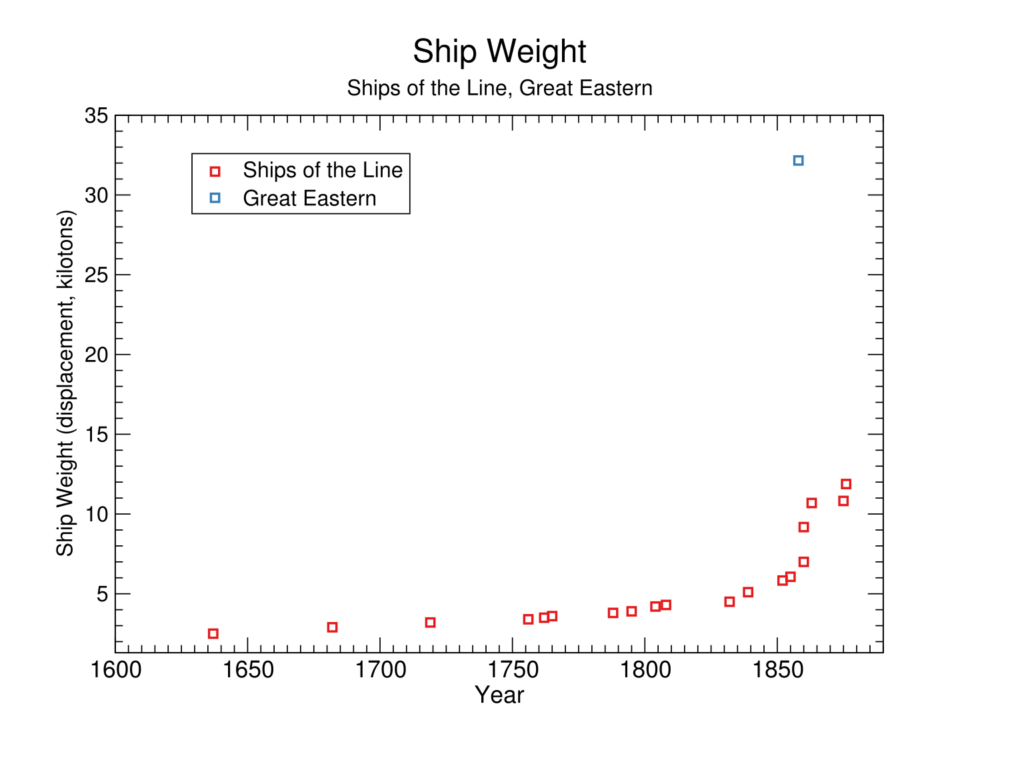

Data

We took displacement and ‘estimated displacement’ data from the same Wikipedia table17 for Royal Navy first-rate line-of-battle ships and put it in this spreadsheet, sheet ‘Displacement calculations’. Figure 5 below shows this data.

Discontinuity Measurement

If we model this data as a linear trend through 1795 followed by an exponential trend,18 then compared to previous rates in these trends, tonnage contained six greater than ten year discontinuities, shown in the table below.19

| Year | Displacement (tons) | Discontinuity | Ship Surname |

| 1804 | 4,200 | 17 years | Hibernia |

| 1839 | 5,100 | 35 years | Queen |

| 1852 | 5,829 | 25 years | Duke of Wellington |

| 1860 | 7,000 | 30 years | Victoria |

| 1860 | 9,180 | 59 years | Warrior |

| 1863 | 10,690 | 23 years | Minotaur |

In addition to the sizes of these discontinuities in years, we have tabulated a number of other potentially relevant metrics here.20

Once again, if we model the data as hyperbolic, it contains no discontinuities of more than ten years, however this is unsurprising after about 1859 end given the proximity of the asymptote (see further explanation in previous section, and calculations in the spreadsheet, sheet ‘Displacement calculations’).

The SS Great Eastern

In the process of another investigation, we noted that a civilian ship, the SS Great Eastern, launched in 1858, was about six times larger by volume than any other ship at the time. It apparently took more than forty years for its length, gross tonnage, and passenger capacity to be surpassed.21 We calculate its tonnage (BOM) to be 22,990 tons (see spreadsheet, tab Tonnage calculations). Supposing our Royal Navy dataset is a good proxy for overall ship size records during this time, and treating past progress as exponential, the SS Great Eastern represents a 416-year discontinuity in tonnage (BOM) over previous Royal Navy ships. (See spreadsheet, tab Tonnage calculations) If the trend is modeled as a hyperbola instead, the SS Great Eastern still represents an 11 year discontinuity, which is as big as a discontinuity can be in the context of the theoretical expectation of arbitrarily large ships when the hyperbola reaches its asymptote in 11 years.22

It is possible that there were other civilian ships prior to the Great Eastern that were also big, making the Great Eastern not a discontinuity. However we think this is unlikely. The RMS Persia, launched only three years prior to the Great Eastern, was the ‘largest’ ship in the world at that time24, and yet was only slightly bigger than the biggest military ships, in terms of tonnage (BOM). (See spreadsheet). If in the intervening two or three years a larger ship appeared, we do not know of it.

Using displacement, recorded on Wikipedia as 32,160 tons, and again assuming that our Royal Navy dataset is a good proxy for all ships, we also get a large discontinuity– 407 years when compared to our previous exponential trend for Royal Navy ships. (See spreadsheet).

We do not know why the Great Eastern was so exceptional. It seems that it was innovative in several ways,25 and that it was designed by a pair of exceptional engineer-scientists, one of whom may have been influential to the design of the Warrior.26 However, the ship’s size might have also been the result of poor business sense, as it appears to have been a financial failure.27

Figure 8: Cutaway of one of the SS Great Eastern‘s engine rooms.28

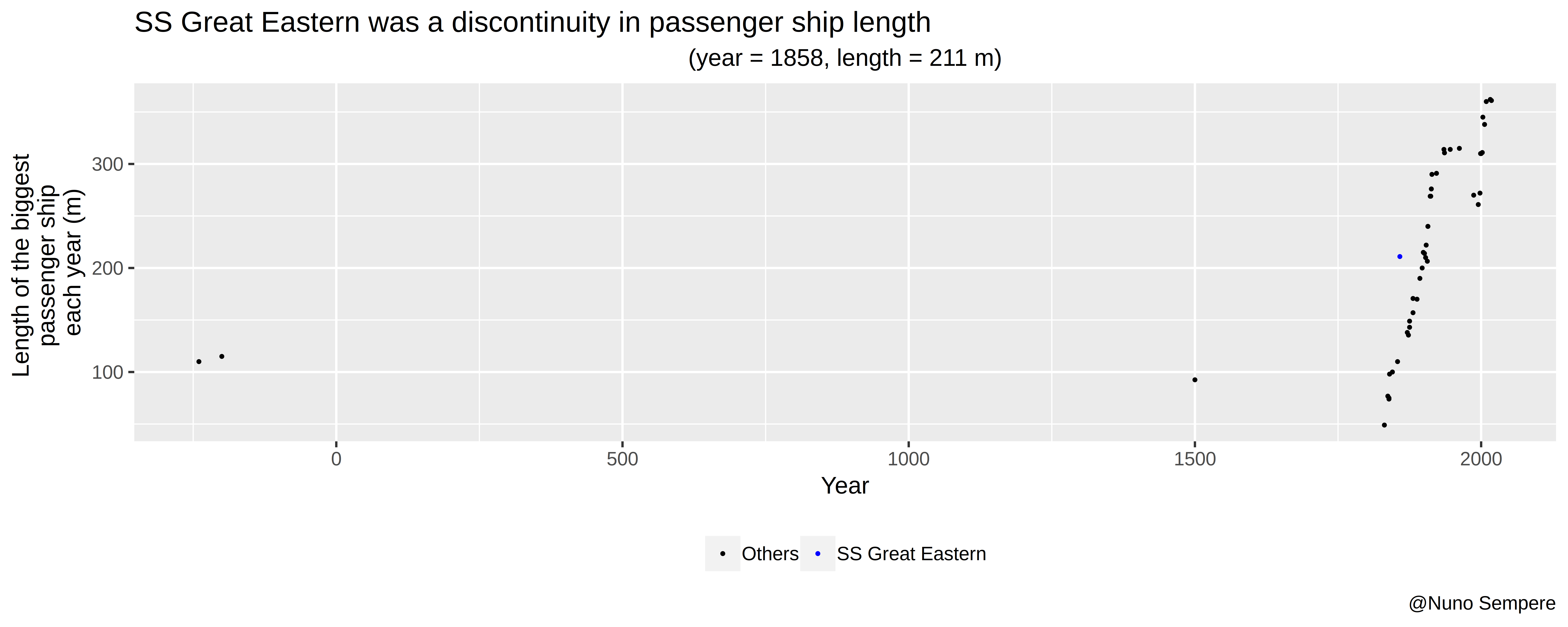

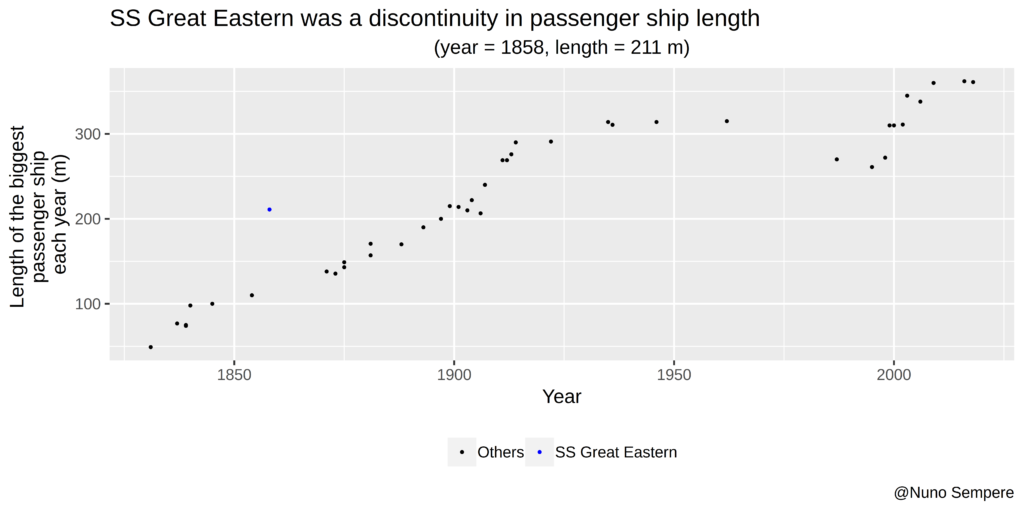

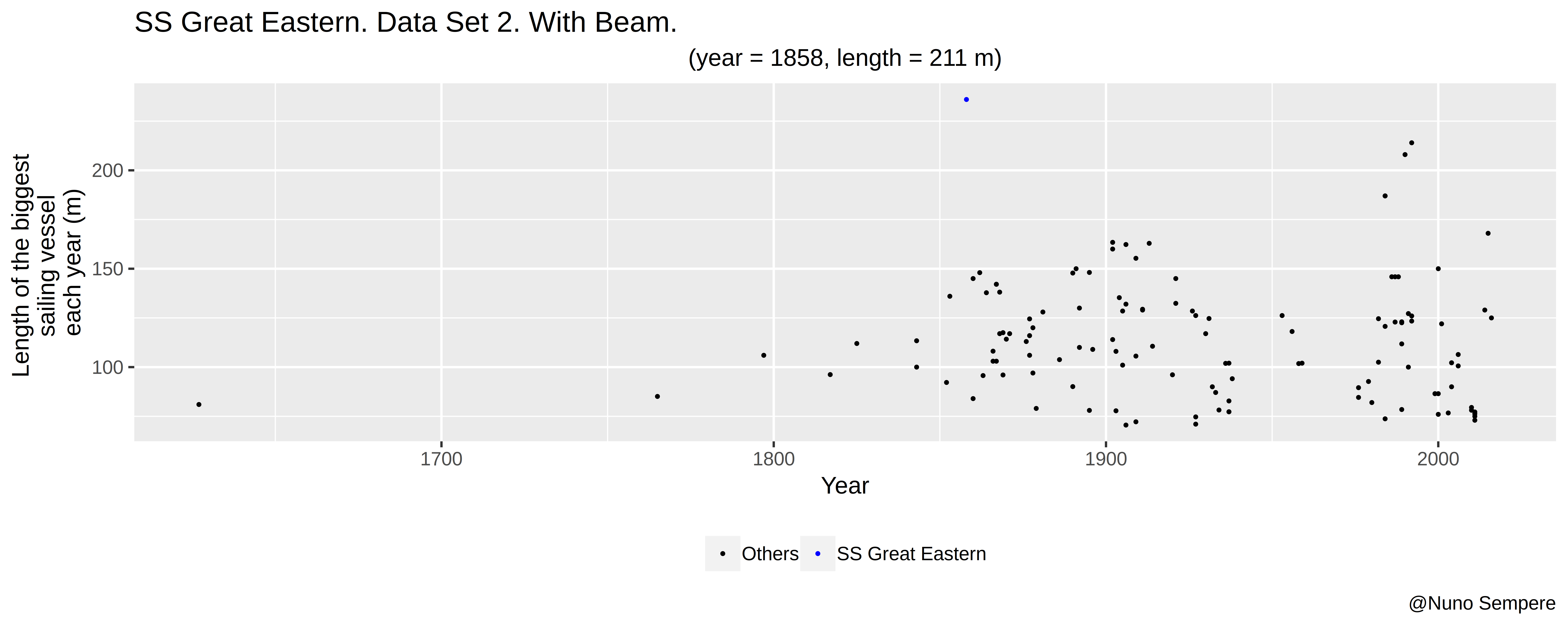

Nuño Sempere has also investigated the Great Eastern as a potential discontinuity to passenger and sailing vessel length trends.29 We learned of this after our own investigation, so have not measured these discontinuities by the same methods as those noted above, nor checked the data. Sempere notes that it took 41 years for the length trend excluding the Great Eastern to surpass it. Figures 9-11 show some of this data.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to bean for his help with this. He blogs about naval history at navalgazing.net.

Notes

- “One consequence of the line of battle was that a ship had to be strong enough to stand in it. In the old type of mêlée battle a small ship could seek out an opponent of her own size, or combine with others to attack a larger one. As the line of battle was adopted, navies began to distinguish between vessels that were fit to form parts of the line in action, and the smaller ships that were not. By the time the line of battle was firmly established as the standard tactical formation during the 1660s, merchant ships and lightly armed warships became less able to sustain their place in a pitched battle. In the line of battle, each ship had to stand and fight the opposing ship in the enemy line, however powerful she might be. The purpose-built ships powerful enough to stand in the line of battle came to be known as a ship of the line.”

“Sailing Ship Tactics.” Wikipedia. February 08, 2019. Accessed April 23, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sailing_ship_tactics. - “the only effective weapons against a big ship were big guns, which required a big ship to carry them.”

“Naval Gazing Main/A Brief History of the Destroyer.” Accessed October 26, 2019. https://www.navalgazing.net/A-Brief-History-of-the-Destroyer.

- “Builder’s Old Measurement (BOM, bm, OM, and o.m.) is the method used in England from approximately 1650 to 1849 for calculating the cargo capacity of a ship.”

“Builder’s Old Measurement.” Wikipedia. December 27, 2018. Accessed April 22, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Builder’s_Old_Measurement. - “File: Weight Growth of RN First Rate Line-of-Battle Ships 1630-1875.Svg.” In Wikipedia. Accessed October 26, 2019. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Weight_Growth_of_RN_First_Rate_Line-of-Battle_Ships_1630-1875.svg.

- “File: Weight Growth of RN First Rate Line-of-Battle Ships 1630-1875.Svg.” In Wikipedia. Accessed October 26, 2019. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Weight_Growth_of_RN_First_Rate_Line-of-Battle_Ships_1630-1875.svg.

- See our spreadsheet, sheet ‘Tonnage calculations’ to see the trends, and our methodology page for details on how we divide the data into trends and how to interpret the spreadsheet.

- See our methodology page for explanation of how we calculated these numbers. Also see our spreadsheet, sheet ‘Tonnage calculations’ for these calculations.

- See our methodology page for more details.

- “Although the Royal Navy had been using steam power in smaller ships for three decades, it had not been adopted for ships of the line, partly because the enormous paddle-boxes required would have meant a severe reduction in the number of guns carried. This problem was solved by the adoption of the screw propeller in the 1840s. Under a crash programme announced in December 1851 to provide the navy with a steam-driven battlefleet, the design was further modified by the new Surveyor, Captain Baldwin Walker. The ship was cut apart in two places on the stocks in January 1852, lengthened by 30 feet (9.1 m) overall and given screw propulsion.”

“HMS Duke of Wellington (1852).” Wikipedia. February 08, 2019. Accessed April 22, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Duke_of_Wellington_(1852). - “Warrior and her sister ship HMS Black Prince were the first armour-plated, iron-hulled warships, and were built in response to France’s launching in 1859 of the first ocean-going ironclad warship, the wooden-hulled Gloire.” “HMS Warrior (1860).” Wikipedia. December 18, 2018. Accessed April 23, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Warrior_(1860).

She and her sister ship the Orlando were the longest wooden warships built for the Royal Navy. … The length, the unique aspect of the ship, was actually an Achilles’ heel of the Mersey and Orlando. The extreme length of the ship put enormous strains on her hull due to the unusual merging of heavy machinery, and a lengthy wooden hull, resulting in her seams opening up. They were pushing the limits of what was possible in wooden ship construction:

Even the biggest of the 5,000-6,000-ton wooden battleships of the mid-to-late 19th century and the 5,000-ton wooden motorships constructed in the United States during World War I did not exceed 340 feet in length or 60 feet in width. The longest of these ships, the Mersey-class frigates, were unsuccessful, and one, HMS Orlando, showed signs of structural failure after an 1863 voyage to the United States. The Orlando was scrapped in 1871 and the Mersey soon after. Both the Mersey-class frigates and the largest of the wooden battleships, the 121-gun Victoria class, required internal iron strapping to support the hull, as did many other ships of this kind. In short, the construction and use histories of these ships indicated that they were already pushing or had exceeded the practical limits for the size of wooden ships.[1]

Britain had built two long frigates in 1858 – HMS Mersey and HMS Orlando – the longest, largest and most powerful single-decked wooden fighting ships. Although only 335 feet long, they suffered from the strain of their length, proving too weak to face a ship of the line in close quarters.[2]

“HMS Mersey (1858).” Wikipedia. August 29, 2017. Accessed April 24, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Mersey_(1858).

- “Brunel’s Great Eastern represented the next great development in shipbuilding. Built in association with John Scott Russell, it used longitudinal stringers for strength, inner and outer hulls, and bulkheads to form multiple watertight compartments.”

“Shipbuilding.” Wikipedia. April 18, 2019. Accessed April 23, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shipbuilding#Industrial_Revolution.

“The hull was an all-iron construction, a double hull of 19 mm (0.75 in) wrought iron in 0.86 metres (2 feet 10 inches) plates with ribs every 1.8 m (5.9 ft). Internally, the hull was divided by two 107 m (351 ft) long, 18 m (59 ft) high, longitudinal bulkheads and further transverse bulkheads dividing the ship into nineteen compartments.”

“SS Great Eastern.” Wikipedia. April 22, 2019. Accessed April 23, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Great_Eastern. - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, s.v. “Builder’s Old Measurement,” (accessed April 5, 2019)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Builder%27s_Old_Measurement - “File: Weight Growth of RN First Rate Line-of-Battle Ships 1630-1875.Svg.” In Wikipedia. Accessed October 26, 2019. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Datei:Weight_Growth_of_RN_First_Rate_Line-of-Battle_Ships_1630-1875.svg.

- See our spreadsheet, sheet ‘Displacement calculations’ to see the trends, and our methodology page for details on how we divide the data into trends and how to interpret the spreadsheet.

- See our methodology page for explanation of how we calculated these numbers. Also see our spreadsheet, sheet ‘Displacement calculations’ for these calculations.

- See our methodology page for more details.

- ” She was by far the largest ship ever built at the time of her 1858 launch, and had the capacity to carry 4,000 passengers from England to Australia without refueling. Her length of 692 feet (211 m) was only surpassed in 1899 by the 705-foot (215 m) 17,274-gross-ton RMS Oceanic, her gross tonnage of 18,915 was only surpassed in 1901 by the 701-foot (214 m) 21,035-gross-ton RMS Celtic, and her 4,000-passenger capacity was surpassed in 1913 by the 4,935-passenger SS Imperator. The ship’s five funnels were rare. These were later reduced to four.” “These measurements were six times larger by volume than any ship afloat…”

“SS Great Eastern.” Wikipedia. April 22, 2019. Accessed April 23, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Great_Eastern. - The Great Eastern was the first ship to use a double-skinned hull:

“Great Eastern was the first ship to incorporate the double-skinned hull, a feature which would not be seen again in a ship for several decades, but which is now compulsory for reasons of safety. ” We understand that it was also one of the first European ships to be divided into watertight compartments using internal bulkheads, one of the first iron-hulled ships, and one of the first ships to use screw propulsion (although it also had sails and paddlewheels) “SS Great Eastern.” Wikipedia. April 22, 2019. Accessed April 23, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Great_Eastern. - “During the 1850s he argued within the Navy for the construction of iron warships and the first design, HMS Warrior, is said by some to be a “Russell ship”.[25][26] ”

“John Scott Russell.” Wikipedia. March 29, 2019. Accessed May 01, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Scott_Russell.“Isambard Kingdom Brunel FRS (/ˈɪzəmbɑːrd bruːˈnɛl/; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859[1]), was an English mechanical and civil engineer who is considered “one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history”,[2] “one of the 19th-century engineering giants”,[3] and “one of the greatest figures of the Industrial Revolution, [who] changed the face of the English landscape with his groundbreaking designs and ingenious constructions”.[4]“

“Isambard Kingdom Brunel.” Wikipedia. April 11, 2019. Accessed May 01, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isambard_Kingdom_Brunel. - In what appears to be part of a pattern of financial problems, the ship’s maiden voyage brought in considerably less revenue than expected: “From a financial perspective, the American venture had been a disaster; the ship had taken in only \$120,000 against a \$72,000 overhead, whereas the company had expected to take in \$700,000. In addition, the company was facing a daily interest payment of \$5,000, which ate into any profits the ship made." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Great_Eastern

- This 3D reconstruction image was made by Simon Edwards at History Rebuilt. Reproduced with permission.

- Sempere, Nuño. “Discontinuous Progress in Technological Trends.” In brightest day, in blackest night. Accessed May 10, 2020. https://nunosempere.github.io/rat/Discontinuous-Progress.html.