Table of Contents

Incomplete case studies of discontinuous progress

Published 07 February, 2020; last updated 08 March, 2021

This is a list of potential cases of discontinuous technological progress that we have investigated partially or not at all.

List

In the course of investigating cases of potentially discontinuous technological progress, we have collected around fifty suggested instances that we have not investigated fully. This is a list of them and what we know about them.

The Haber Process

This was previously listed as NSD, but that is tentatively revoked while we investigate a complication with the data.

Previous explanation

The Haber process was the first energy efficient method of producing ammonia, which is key to making fertilizer. The reason to expect that the Haber process might represent discontinuous technological progress is that previous processes were barely affordable, while the Haber process was hugely valuable—it is credited with fixing much of the nitrogen now in human bodies—and has been used on an industrial scale since 1913.

A likely place to look for discontinuities then is in the energy cost of fixing nitrogen. Table 4 in Grünewald’s Chemistry for the Future suggests that the invention of the Haber reduced the energy expense by around 60% per nitrogen bonded over a method developed eight years earlier. The previous step however appears to have represented at least a 50% improvement over the process of two years earlier (though the figure is hard to read). Later improvements to the Haber process appear to have been comparable. Thus it seems the Haber process was not an unusually large improvement in energy efficiency, but was probably instead the improvement that happened to take the process into the range of affordability.

Since it appears that energy was an important expense, and the Haber process was especially notable for being energy efficient, and yet did not represent a particular discontinuity in energy efficiency progress, it seems unlikely that the Haber process involved a discontinuity. Furthermore, it appears that the world moved to using the Haber process over other sources of fertilizer gradually, suggesting there was not a massive price differential, nor any sharp practical change as a result of the adoption of the process. In the 20’s the US imported much nitrogen from Chile. Alternative nitrogen source calcium cyanamide reached peak production in 1945, thirty years since the Haber process reached industrial scale production.

The amount of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer applied hasn’t abruptly changed since 1860 (see p24). Neither has the amount of food produced, for a few foods at least.

In sum, it seems the Haber process has had a large effect, but it was produced by a moderate change in efficiency, and manifest over a long period.

Aluminium

It is sometimes claimed that the discovery of the Hall–Héroult process in the 1880s brought the price of aluminium down precipitously. We found several pieces of quantitative data about this, but they seriously conflict. The most rigorous looking is a report from Patricia Plunkert at the US Geological Survey, from which we get the following data. However note that some of these figures may be off by orders of magnitude, according to other sources.

Plunkert provides a table of historic aluminium prices, according to which the nominal price fell from \$8 per pound to \$0.58 per pound sometime between 1887 and 1895 (during most of which time no records are available). This period probably captures the innovation of interest, as the Hall–Héroult process was patented in 1886 according to Plunkert, and the price only dropped by \$1 per pound during the preceding fifteen years according to her table. Plunkert also says that the price was held artificially low to encourage consumers in the early 1900s, suggesting the same may have been true earlier, however this seems likely to be a small correction.

The sewing machine

Early sewing machines apparently brought the time to produce clothing down by an order of magnitude (from 14 hours to 75 minutes for a man’s dress shirt by one estimate). However it appears that the technology progressed more slowly, then was taken up by the public later – probably when it became cost-effective, at which time adoptees may have experienced a rapid reduction in sewing time (presumably at some expense). These impressions are from a very casual perusal of the evidence.

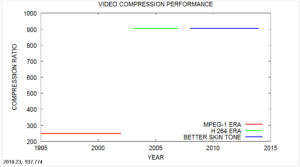

Video compression

Blogger John McGowan claims that video compression performance was constant at a ratio of around 250 for about seven years prior to 2003, then jumped to around 900.

Information storage volume

According to the Performance Curves Database (PCDB), ‘information storage volume’ for both handwriting and printing has grown by a factor of three in recent years, after less than doubling in the hundred years previously. It is unclear what exactly is being measured here however.

Undersea cable price

The bandwidth per cable length available for a dollar apparently grew by more than 1000 times in around 1880.

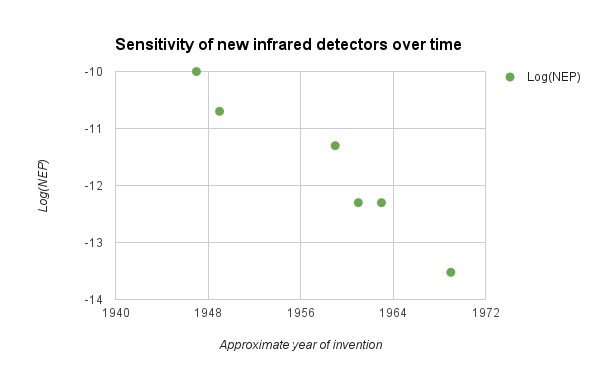

Infrared detector sensitivity

We understand that infrared detector sensitivity is measured in terms of ‘Noise Equivalent Power’ (NEP), or the amount of power (energy per time) that needs to hit the sensor for the sensor’s output to have a signal:noise ratio of one. We investigated progress in infrared detection technology because according to Academic Press (1974), the helium-cooled germanium bolometer represented a four order of magnitude improvement in sensitivity over uncooled detectors.1 However our own investigation suggests there were other innovations between uncooled detectors and the bolometer in question, and thus no abrupt improvement.

We list advances we know of here, and summarize them in Figure 5. The 1947 point is uncooled. The 1969 point is nearly four orders of magnitude better. However we know of at least four other detectors with intermediate levels of sensitivity, and these are spread fairly evenly between the uncooled device and the most efficient cooled one listed.

We have not checked whether the progress between the uncooled detector and the first cooled detector was discontinuous, given previous rates. This is because we have no strong reason to suspect it is.

Genome sequencing – IIP

This appears to have seen at least a moderate discontinuity. An investigation is in progress.

It was suggested to us in particular that Next Generation Sequencing produced discontinuous progress in output per instrument run for DNA sequencing.

Aircraft shot down per shell fired

We’ve seen it claimed that the proximity fuse increased this metric by 2x or more. We don’t know what the trend was beforehand, however.

Time to produce clothing

The Sewing machine was proposed as discontinuous in this metric. We have not investigated.

Sensitivity of infrared detectors

Cryogenically cooled semiconductor sensors were proposed as discontinuous in this metric. We have not investigated.

Frames per Second

It was suggested that something in high sensitivity, high precision metrology, e.g. trillion frame-per-second camera from MIT, would be discontinuous in this metric. We have not investigated.

Access to Information

Smart phones were suggested as a discontinuity in this metric. We have not investigated.

Spread of minimally invasive surgery

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was suggested as a discontinuity in this metric. We have not investigated.

Max. submerged endurance, submerged runs

Nuclear-powered submarines may be a discontinuity in this metric. We have not investigated.

Clothmaking efficiency

The Jacquard Loom and the Spinning Jenny were suggested as discontinuities in this metric. We have not investigated.

Personal armor protectiveness-to-weight ratio

Kevlar was suggested as discontinuities in this metric. We have not investigated.

Lumens per watt

High pressure sodium lamps were suggested as discontinuities in this metric. We have not investigated.

Linear programming

The Simplex algorithm was suggested as discontinuities in this metric. We have not investigated.

Fourier transform speed

Fast fourier transform was suggested as discontinuities in this metric. We have not investigated.

Polynomial identity testing efficiency

Probabilistic testing methods were suggested as discontinuities in this metric. We have not investigated.

Audio compression efficiency

The MP3 format was suggested as discontinuities in this metric. We have not investigated.

Crop yields

This amazing genetic modification, if it works as claimed, may well be a discontinuity in this metric. We have not investigated.

Thanks to Stephen Jordan, Bren Worth, Finan Adamson and others for suggesting potential discontinuities in this list.

- ‘Following Johnson’s work at shorter wavelengths, photometric systems were established at the University of Arizona for each of the infrared windows from 1 to 25μm. At 5, 10, and 22μm, the helium-cooled germanium bolometer was used. This detector provided four orders of magnitude improvement in sensitivity over uncooled detectors and was utilized at wavelengths out to 1000μm.’ – Academic press, 1974