Table of Contents

Penicillin and historic syphilis trends

Published 07 February, 2020; last updated 28 May, 2020

Penicillin did not precipitate a discontinuity of more than ten years in deaths from syphilis in the US. Nor were there other discontinuities in that trend between 1916 and 2015.

The number of syphilis cases in the US also saw steep decline but no substantial discontinuity between 1941 and 2008.

On brief investigation, the effectiveness of syphilis treatment and inclusive costs of syphilis treatment do not appear to have seen large discontinuities with penicillin, but we have not investigated either thoroughly enough to be confident.

Details

This case study is part of AI Impacts’ discontinuous progress investigation.

Background

Penicillin was first used to treat a patient in 19411 and became mass-produced in the US between 1942 and 1944.2 It quickly became the preferred treatment for syphilis, and appears to be generally credited with producing a steep decline in the prevalence of syphilis which was seen at around that time.3 4

Trends

We consider four metrics of success in treating syphilis: the number of syphilis cases, the number of syphilis deaths, effectiveness of syphilis treatment, and the inclusive cost of treatment.

In addition to the size of any discontinuities in years, we tabulated a number of other potentially relevant statistics for each metric here.

US Syphilis cases

Data

Figure 1 shows historic reported syphilis cases after 1941, according to the CDC.6 We converted the data in the figure into this spreadsheet.7

Figure 1: Syphilis—Reported Cases by Stage of Infection, United States, 1941–2009, according to the CDC8

Discontinuity Measurement

According to this data, total cases of syphilis declined by around 80% over fifteen years (see Figure 1). We do not see any substantial discontinuities, with 1944 seeing the largest change, equal to only 4 years of progress at the previous rate. Unfortunately, we were unable to find quantitative data prior to 1941, so we were only able to track progress for the three years leading up to the mass production of penicillin.

From our perspective, progress by 1943 may already have been affected by availability of penicillin that we do not know about, in which case we have no earlier trend to go by. However we note that the scale of annual reductions following penicillin is not larger than the increase seen in 1943, and not vastly larger than later annual variations, so the largest abrupt decrease from penicillin seems unlikely to have been large compared to the usual scale of variation.

US Deaths from syphilis

Data

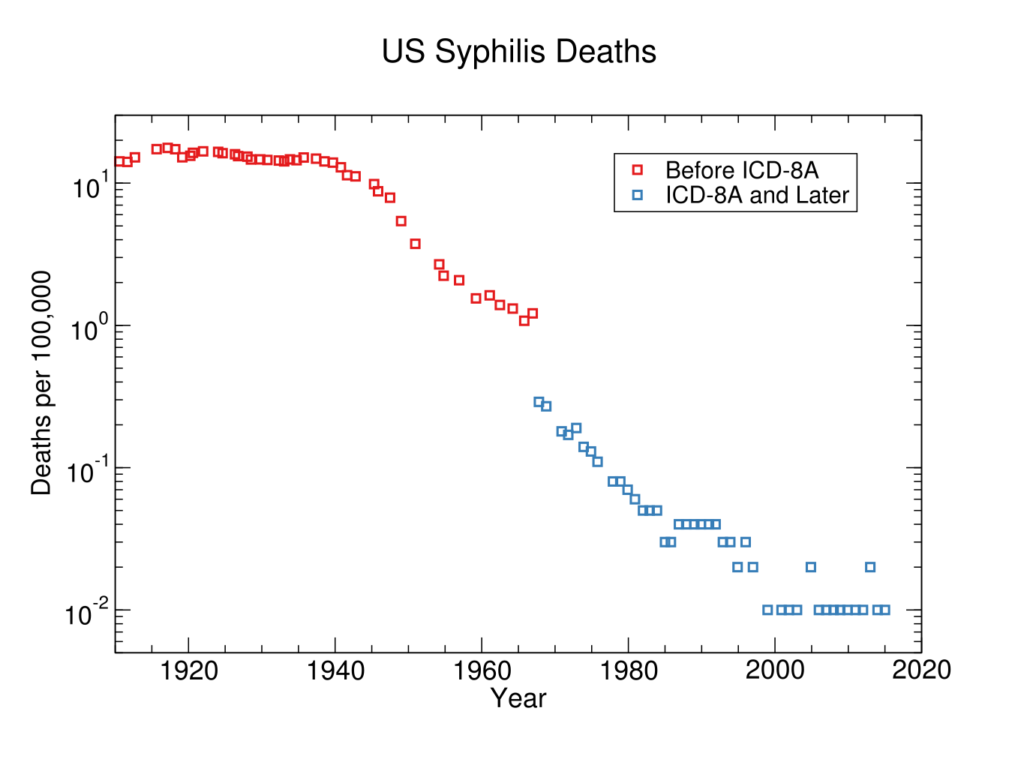

We collected data from two graphs of historical US syphilis deaths and put it in this spreadsheet. The first is shown in Figure 2, and comes from Armstrong et al.’s 1999 report on infectious disease mortality in the United States.9 The authors collected it from historical mortality and population data from the CDC and public use mortality data tapes.10 We used an automatic figure data extraction tool to extract data from the figure.11 Mortality rates after the mid-60s are indistinguishable from zero in this figure, so we do not include them. Instead we include records of total US deaths from Peterman & Kidd, 201912, which we combine with US population data to get mortality rates between 1957 and 2015.

Figure 2: Syphilis mortality rate in the US during the 20th century.13

Discontinuity Measurement

We calculate discontinuities in our spreadsheet, according to this methodology. There were no substantial discontinuities in progress for reducing syphilis deaths in the US during the time for which we have data. The largest positive deviation from a previous trend was a drop representing five years of progress in around 1940, two years before even enough ‘US penicillin’ was available to treat ten people.14

In sum, while deaths from syphilis rapidly declined around the 1940s, this progress was not discontinuous at the scale of years. And while penicillin seems likely to have helped in this decline, it did not yet exist to contribute to the most discontinuously fast progress in that trend (and that progress was still not rapid enough to count as a substantial discontinuity for this project).

Discussion of causes

The decline of syphilis mortality does not appear to be entirely from penicillin, since it is underway by 1940, just prior to the mass-production of penicillin. This is strange, so it is plausible that we misunderstand some aspect of the situation.

The only other factor we know about is US Surgeon General Thomas Parran’s launch of a national syphilis control campaign in 1938.15 Wikipedia also attributes some of the syphilis decline over the 19th and 20th centuries to decreasing virulence of the spirochete, but we don’t know of any reason for that to especially coincide with the 1940s decline.16

Effectiveness at treating syphilis

Even if penicillin’s effect on the US death rate from syphilis was gradual, we might expect this to be due to frictions like institutional inertia, rather than from gradual progress in the underlying technology. It might still be that penicillin was a radically better drug than its predecessors, when applied.

We briefly investigated whether penicillin might have represented discontinuous progress in effectiveness at curing syphilis, and conclude that it probably did not, because it does not appear to have been clearly better than its predecessor in terms of cure rates. In a 1962 review of treatment of ‘early’ syphilis17, Willcox writes that ‘a seronegativity-rate of 85 per cent. at 11 months had been achieved’ in 1944 after penicillin became the primary treatment for syphilis, but also says that the previously common treatment—arsenic and bismuth—was successful in more than 90% of cases in which it was carried out.18

Willcox explains that the major downsides of the earlier treatment were very high defection rates (with perhaps as few as a quarter of patients completing the treatment), and ‘serious toxic effects’.19 We have not checked that exactly the same notion of success is being used in these figures, have not assessed the reliability of this source, and do not know how important treatment for ‘early’ syphilis is relative to treatment for all syphilis, so it could still be that penicillin was a more effective treatment overall. However we did not investigate this further.

Inclusive costs of treatment

Penicillin apparently allowed most patients to receive a curative dose of medicine, whereas ‘arsenic and bismuth therapy’ achieved this for perhaps as few as a quarter of patients.20 If penicillin made an abrupt difference to syphilis treatment then, it seems likely to have been in terms of inclusive costs (which were partly reflected in willingness to be treated).

Qualitatively, the costs of treatment do seem to have been much lower. The time for treatment dropped from a year to around eight days.21 Our impression is that the side effects qualitatively reduced from horrible and sometimes deadly to apparently bearable.

However even if penicillin was a large improvement over its predecessors in absolute terms (which seems likely), it would be hard to make a clear case that it was large relative to previous progress in syphilis treatments, because recent progress was also incredible.

The ‘arsenic and bismuth therapy’ mentioned above, that preceded penicillin, seems to have been a combination of the arsenic-based drug salvarsan (arsphenamine) and similar drugs developed subsequently, with bismuth. 22 Salvarsan (arsphenamine) was considered such radical improvement over its own predecessors that it was known as the ‘magic bullet’, and won its discoverer Paul Erhlich a Nobel prize.23 A physician at the time describes24:

“Arsenobenzol, designated “606,” whatever the future may bring to justify the present enthusiasm, is now actually a more or less incredible advance in the treatment of syphilis and in many ways is superior to the old mercury – as valuable as this will continue to be – because of its eminently powerful and eminently rapid spirochaeticidal property.”

It is easy to see how salvarsan could be hugely costly to take, yet still represent large progress over earlier options, when we note that the common treatment prior to salvarsan was mercury,25 which had ‘terrible side effects’ including the death of many patients, characteristically took years, and was not obviously helpful.26

So at a glance penicillin doesn’t look to have been clearly discontinuous relative to the impressive recent trend, and measuring inclusive costs is hard to do finely enough to see less clear discontinuities. Thus evaluating these costs quantitatively will remain beyond the scope of this investigation at present. We tentatively guess that penicillin did not represent a large discontinuity in inclusive costs of syphilis treatment, though it did represent huge progress.

Conclusions

Penicillin probably made quick but not abrupt progress in reducing syphilis and syphilis mortality. Penicillin doesn’t appear to have been much more likely to cure a patient than earlier treatments, conditional on the treatment being carried out, but it penicillin treatment appears to have been around four times more likely to be carried out, due to lower costs. Qualitatively penicillin represented an important reduction in costs, but it is hard to evaluate this precisely or compare it with the longer term progress. It appears that as recently as 1910 another drug for syphilis also represented qualitatively huge progress in treatment, so it is unlikely that penicillin was a large discontinuity relative to past progress.

Notes

- “In 1940, Florey carried out vital experiments, showing that penicillin could protect mice against infection from deadly Streptococci. Then, on February 12, 1941, a 43-year old policeman, Albert Alexander, became the first recipient of the Oxford penicillin.”

American Chemical Society. “Alexander Fleming Discovery and Development of Penicillin – Landmark.” Accessed January 15, 2020. https://www.acs.org/content/acs/en/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/flemingpenicillin.html.

- “On March 14, 1942, the first patient was treated for streptococcal sepsis with US-made penicillin produced by Merck & Co.[38] Half of the total supply produced at the time was used on that one patient, Anne Miller.[39] By June 1942, just enough US penicillin was available to treat ten patients.[40] In July 1943, the War Production Board drew up a plan for the mass distribution of penicillin stocks to Allied troops fighting in Europe.[41] The results of fermentation research on corn steep liquor at the Northern Regional Research Laboratory at Peoria, Illinois, allowed the United States to produce 2.3 million doses in time for the invasion of Normandy in the spring of 1944…As a direct result of the war and the War Production Board, by June 1945, over 646 billion units per year were being produced.” “Penicillin,” in Wikipedia, May 23, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Penicillin&oldid=898359231.

- e.g. “Within years, widespread use of penicillin for treatment of all stages of syphilis (primary, secondary, tertiary, latent) resulted in dramatic decreases in the incidence of syphilis and associated mortality.”

John M. Douglas, “Penicillin Treatment of Syphilis,” JAMA 301, no. 7 (February 18, 2009): 769–71, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.143. - “Today, with the dawn of the space-age, there are few who would disagree with the remark of Professor Smelov (1956) at the First International Symposium on Venereal Diseases and Treponematoses in Washington, D.C., U.S.A., that “hardly any one doubts the curative power of penicillin against

syphilis”, or the opinion of Kinaqigil (1956) of Turkey expressed at the same meeting that penicillin is preferable to all other drugs in this condition. Since Mahoney and his colleagues first used this new antibiotic in the treatment of syphilis (Mahoney, Arnold, and Harris, 1943a, b, 1949), 18 years have passed and little has occurred to shake the faith of

many thousands of doctors and of millions of patients in the potency of penicillin in this serious disease (see Doliken, 1954; Danbolt, 1954; Perdrup, Heilesen, and Sylvest, 1954; Shafer, Usilton, and Price, 1954) (Table I). Indeed, no other testimonial is required than the striking fall in the incidence of early syphilis which has occurred throughout the world.”

R. R. Willcox, “Treatment of Early Venereal Syphilis with Antibiotics*,” British Journal of Venereal Diseases 38, no. 3 (September 1962): 109–25.

- From Wikimedia Commons: Science History Institute [Public domain]

- Figure 1 is Figure 33 from Division of STD Prevention, “Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2009,” November 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20170120091355/https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/surv2009-Complete.pdf.

- We used an automatic figure data extraction tool to extract the data from the figure. Here is a link to a .tar file that can be loaded into this tool to reproduce our extraction.

- From Figure 33 in Division of STD Prevention, “Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2009,” November 2010, https://web.archive.org/web/20170120091355/https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/surv2009-Complete.pdf.

- Table 4D in Gregory L. Armstrong, Laura A. Conn, and Robert W. Pinner, “Trends in Infectious Disease Mortality in the United States During the 20th Century,” JAMA 281, no. 1 (January 6, 1999): 61–66, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.1.61.

- “Data were obtained from yearly tabulations of causes of death on file at the Division of Vital Statistics of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics and from public use mortality data tapes from 1962 through 1996. … Population data used in the calculation of mortality rates were also obtained from the National Center for Health Statistics. The data for years prior to 1933 included only the population of the death-registration states or death-registration area, corresponding to the scope of the mortality data being used.” – Armstrong, Gregory L. 1999. “Trends In Infectious Disease Mortality In The United States During The 20Th Century”. JAMA 281 (1): 61. American Medical Association (AMA). doi:10.1001/jama.281.1.61.

- The tool was at https://apps.automeris.io/wpd/. We also extracted data between 1917 and 1967 manually using the same tool. Here is a link to a .tar file that can be loaded into the tool here to reproduce our extraction.

- Peterman, Thomas A., and Sarah E. Kidd. “Trends in Deaths Due to Syphilis, United States, 1968-2015.” Sexually Transmitted Diseases 46, no. 1 (2019): 37–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000899.

- See Figure 4D in Gregory L. Armstrong, Laura A. Conn, and Robert W. Pinner, “Trends in Infectious Disease Mortality in the United States During the 20th Century,” JAMA 281, no. 1 (January 6, 1999): 61–66, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.1.61.

- “On March 14, 1942, the first patient was treated for streptococcal sepsis with US-made penicillin produced by Merck & Co.[38] Half of the total supply produced at the time was used on that one patient, Anne Miller.[39] By June 1942, just enough US penicillin was available to treat ten patients.[40]” “Penicillin,” in Wikipedia, May 23, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Penicillin&oldid=898359231.

- “The serious consequences of syphilis for the population led to its designation as the “shadow on the land” and prompted US Surgeon General Thomas Parran to launch a national syphilis control campaign in 1938 based on public education, serologic testing, treatment, and a national network of sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics.”

Douglas, John M. “Penicillin Treatment of Syphilis.” JAMA 301, no. 7 (February 18, 2009): 769–71. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.143. - “The symptoms of syphilis have become less severe over the 19th and 20th century in part due to widespread availability of effective treatment and partly due to decreasing virulence of the spirochete.[7]“

“Epidemiology of Syphilis.” In Wikipedia, February 9, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Epidemiology_of_syphilis&oldid=882541706. - “Before the discovery of penicillin, reliance had had to be placed on arsenic and bismuth therapy given over periods of approximately one year. The reported results for those patients who completed their treatment (see, for example, Burckhardt, 1949; Degos, Vissian, and Basset, 1950; Thompson and Smith, 1950; Arutyunov and Gurvich, 1958) in large series of cases were good and cure rates exceeding 90 per cent. were reported…

…As soon as it became available, penicillin was soon in use for the treatment of syphilis throughout the world…

…As early as 1946 it became apparent in the U.S.A. that the results were deteriorating. Before May, 1944, a seronegativity-rate of 85 per cent. at 11 months had been achieved, but after that time the figure had fallen to only 60 per cent.”

Willcox, R. R. “Treatment of Early Venereal Syphilis with Antibiotics*.” British Journal of Venereal Diseases 38, no. 3 (September 1962): 109–25. - One of the two great disadvantages of metal-therapy was that, because of the relatively weak treponemicidal powers of the drugs employed, prolonged treatment involving many injections was required, and default from treatment, and therefore absence of cure in those who defaulted, was very common. Indeed, a minimum curative dose might be received by only one quarter of the patients (Chope and Malcolm, 1948). The other disadvantage was the risk of serious toxic effects, which not only curtailed treatment in affected patients but, by reputation, encouraged other patients to default.”

Willcox, R. R. “Treatment of Early Venereal Syphilis with Antibiotics*.” British Journal of Venereal Diseases 38, no. 3 (September 1962): 109–25. - “The out-patient therapy of early syphilis became feasible only with the introduction by Romansky and Rittman (1945) of penicillin in oil-beeswax…by such means, nearly all patients could now achieve a curative dose (Hayman, 1947, Aitken, 1947) instead of only about one-quarter as with arsenic and bismuth (Chope and Malcolm, 1948).”

Willcox, R. R. “Treatment of Early Venereal Syphilis with Antibiotics*.” British Journal of Venereal Diseases 38, no. 3 (September 1962): 109–25. - “Before the discovery of penicillin, reliance had had to be placed on arsenic and bismuth therapy given over periods of approximately one year…

…The use of sixty or more injections of crystalline penicillin G in aqueous solution within a period of 7 1/2 days, if not more than the patients could reasonably tolerate, required their admission to hospital…Good results were reported with eight daily injections of 600,000 units…and success rates of 80 to 85 per cent. were achieved…”

R. R. Willcox, “Treatment of Early Venereal Syphilis with Antibiotics*,” British Journal of Venereal Diseases 38, no. 3 (September 1962): 109–25.

“In 1943 penicillin was introduced as a treatment for syphilis by John Mahoney, Richard Arnold and AD Harris. [22] Mahoney and his colleagues at the US Marine Hospital, Staten Island, treated four patients with primary syphilis chancres with intramuscular injections of penicillin four-hourly for eight days for a total of 1,200,000 units by which time the syphilis had been cured. “John Frith, “Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on Its Origins,” Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 20 (November 1, 2012): 49–58.

- “Arsenicals, mainly arsphenamine, neoarsphenamine, acetarsone and mapharside, in combination with bismuth or mercury then became the mainstay of treatment for syphilis until the advent of penicillin in 1943.”

Frith, John. “Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on Its Origins.” Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 20 (November 1, 2012): 49–58.

- This led in 1910 to the manufacture of arsphenamine, which subsequently became known as Salvarsan, or the “magic bullet”, and later in 1912, neoarsphenamine, Neo-salvarsan, or drug “914”. In 1908 Ehrlich was awarded the Nobel Prize for his discovery. [7, 11, 12]”

John Frith, “Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on Its Origins,” Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 20 (November 1, 2012): 49–58. - John Frith, “Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on Its Origins,” Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 20 (November 1, 2012): 49–58.

- “Mercury stayed in favour as treatment for syphilis until 1910 when Ehrlich discovered the anti-syphilitic effects of arsenic and developed Salvarsan, popularly called the “magic bullet”.”

Frith, John. “Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on Its Origins.” Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 20 (November 1, 2012): 49–58. - “Many physicians doubted the efficacy of mercury, especially as it had terrible side effects and many patients died of mercury poisoning. Beck (1997) describes a typical mercury treatment :

“A patient undergoing the treatment was secluded in a hot, stuffy room, and rubbed vigorously with the mercury ointment several times a day. The massaging was done near a hot fire, which the sufferer was then left next to in order to sweat. This process went on for a week to a month or more, and would later be repeated if the disease persisted. Other toxic substances, such as vitriol and arsenic, were also employed, but their curative effects were equally in doubt.” [9]

Mercury had terrible side effects causing neuropathies, kidney failure, and severe mouth ulcers and loss of teeth, and many patients died of mercurial poisoning rather than from the disease itself. Treatment would typically go on for years and gave rise to the saying,

“A night with Venus, and a lifetime with mercury” [8]”

Frith, John. “Syphilis – Its Early History and Treatment until Penicillin and the Debate on Its Origins.” Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health 20 (November 1, 2012): 49–58.