Table of Contents

Historic trends in transatlantic message speed

Published 07 February, 2020; last updated 23 April, 2020

The speed of delivering a short message across the Atlantic Ocean saw at least three discontinuities of more than ten years before 1929, all of which also were more than one thousand years: a 1465-year discontinuity from Columbus’ second voyage in 1493, a 2085-year discontinuity from the first telegraph cable in 1858, and then a 1335-year discontinuity from the second telegraph cable in 1866.

Details

This case study is part of AI Impacts’ discontinuous progress investigation.

Background

Summary of historic developments

All communications between Europe and North America were carried on ships until 1858, when the first telegraph messages were transmitted over cable between the UK and US.1 That first cable only lasted six weeks, and took more than sixteen hours to send a message from the Queen.2

A permanent cable wasn’t laid until eight years later.3 Better telegraph cables were laid a further thirty and sixty years later. We do not investigate developments after 1929.

Trends

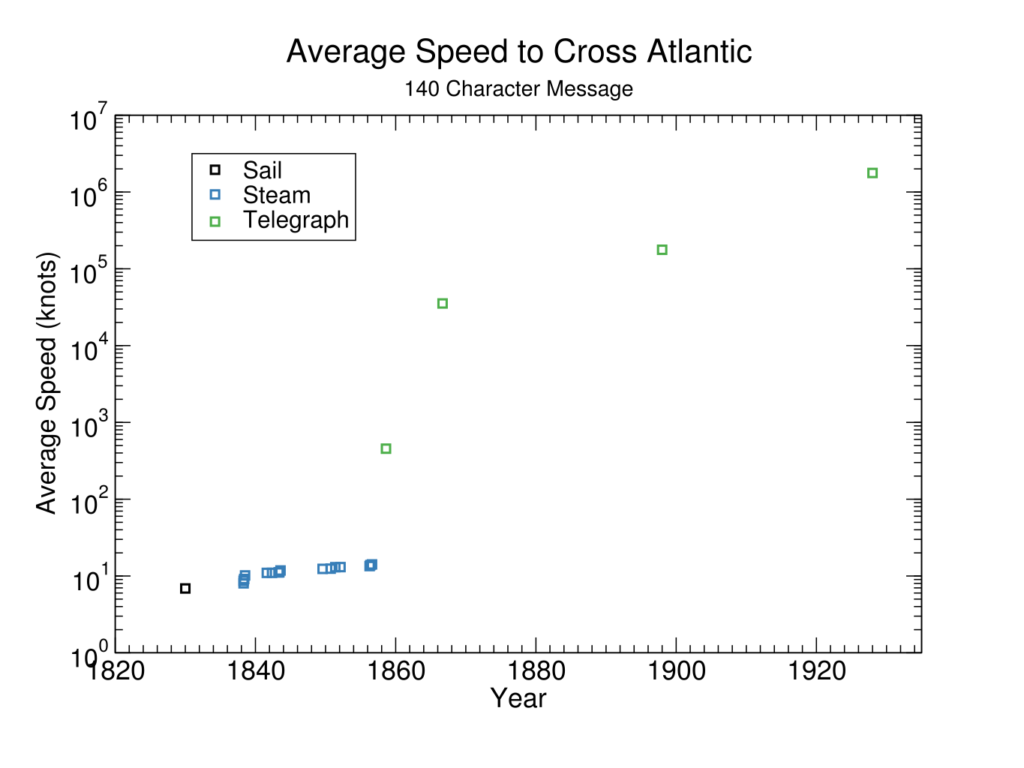

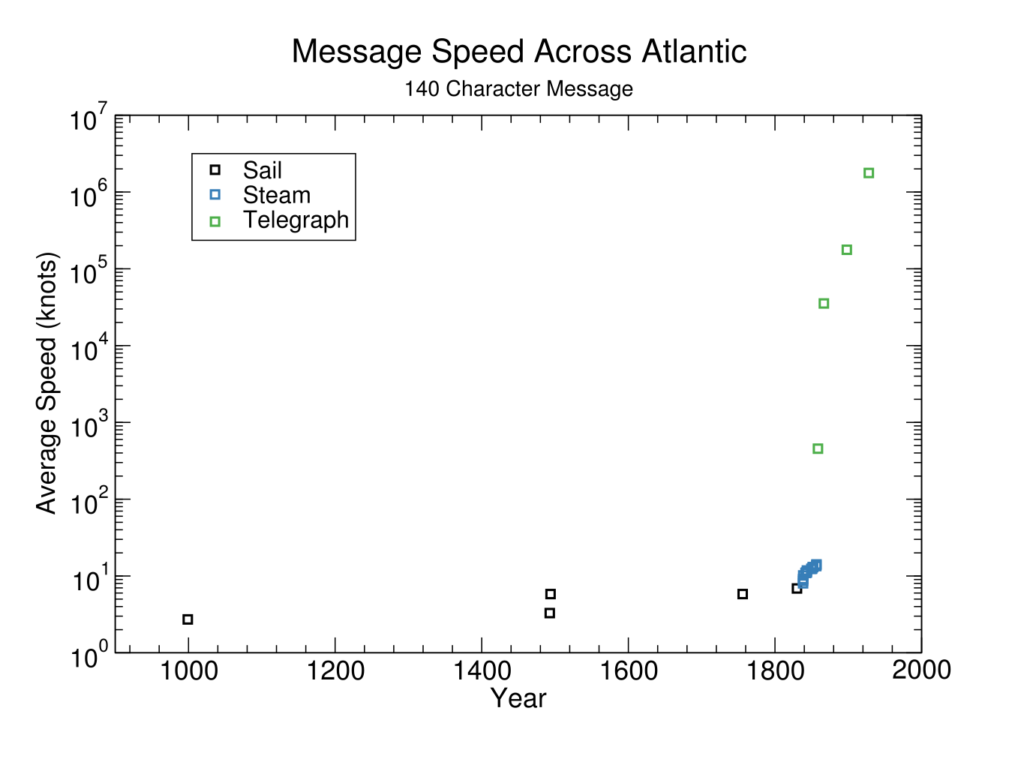

Transatlantic message speed, 140 character message

We looked at historic times to send messages across the Atlantic Ocean.

Message speed can depend on the length of the message. Where this was relevant, we somewhat arbitrarily chose to investigate for a 140 character message. We measure fastest speeds of real historic systems that could send 140 character messages across the Atlantic Ocean. We do not require that a 140 character message was actually sent by the method in question.

We generally use whatever route was actually taken (or supposed in an estimate), and do not attempt to infer faster speeds possible had an optimal route been taken (though note that because we are measuring speed rather than time to cross the Ocean, route length is adjusted for to a first approximation).

We only investigated this metric from 1492-1493 and 1841-1928. We do not investigate 1493-1841 because our data is insufficiently complete to determine how continuous it was.5

Data

Our data for message speed came from a variety of online sources, and has not been thoroughly vetted. The full dataset with sources can be found here.6

Because message delivery coincided with passenger travel until the first telegraph, data until then coincides with that used in our investigation into historic trends in transatlantic passenger travel.

The resulting trend is shown in Figures 2-3.

Discontinuity Measurement

We measure discontinuities by comparing progress made at a particular time to the past trend. For this purpose, we treat the past trend at any given point as exponential or linear depending on apparent fit, and judge a new trend to have begun when the recent trend has diverged sufficiently from the longer term trend. See our spreadsheet, tab ‘Message’ to view the trends, and our methodology page for details on how to interpret our sheets and how we divide data into trends.

Given these judgments about past progress, there were three discontinuities of more than ten years, all of which were more than one thousand years: a 1465-year discontinuity from Columbus’ second voyage in 1493, then a 2085-year discontinuity from the first telegraph cable in 1858, and then a 1335-year discontinuity from the improved telegraph cable in 1866.7 In addition to the size of these discontinuity in years, we have tabulated a number of other potentially relevant metrics here.8.

Discussion of causes

Transatlantic message speed is a narrower metric than overall message speed, precluding some technologies that can only deliver messages short distances or on land (e.g. the semaphore telegraph, which relied on a series of towers within line of sight). We expected this would make discontinuity more likely.

Notes

- ” Exactly 150 years ago, August 1858, the world witnessed a historic event in the history of telecommunications: the successful transmission of telegraph messages across the Atlantic Ocean. Although the transatlantic cable carrying these messages failed after a few weeks of operation, and it wasn’t until 1866 that permanent transatlantic telegraph cable transmission became possible, the 1858 transmissions were heralded worldwide as a major achievement, introducing a new Age of Information. ” Schwartz, Mischa. “History of Communications.” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 46, no. 8, 2008, pp. 26–29., doi:10.1109/mcom.2008.4597099.

- “The celebrations hit a sour note as the fireworks set fire to City Hall. Far worse news was to come, as the cable itself failed completely after six weeks. The cable never really worked well; the Queen’s message had taken 16-1/2 hours to transmit.” Schwartz, Mischa. “History of Communications.” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 46, no. 8, 2008, pp. 26–29., doi:10.1109/mcom.2008.4597099.

- “…and it wasn’t until 1866 that permanent transatlantic telegraph cable transmission became possible”

Schwartz, Mischa. “History of Communications.” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 46, no. 8, 2008, pp. 26–29., doi:10.1109/mcom.2008.4597099.

- See historic trends in transatlantic passenger travel for discussion of this.

- See our methodology page for more details.