Table of Contents

Effect of Eli Whitney’s cotton gin on historic trends in cotton ginning

Published 07 February, 2020; last updated 26 May, 2020

We estimate that Eli Whitney’s cotton gin represented a 10 to 25 year discontinuity in pounds of cotton ginned per person per day, in 1793. Two innovations in 1747 and 1788 look like discontinuities of over a thousand years each on this metric, but these could easily stem from our ignorance of such early developments. We tentatively doubt that Whitney’s gin represented a large discontinuity in the cost per value of cotton ginned, though it may have represented a moderate one.

Details

This case study is part of AI Impacts’ discontinuous progress investigation.

Background

Cotton fibers grow around cotton seeds, which they need to be separated from before use. This can be done by hand, but since 500 C.E.,1 and plausibly prehistory, a variety of tools have aided in speeding up the process. 2

These tools are called ‘cotton gins’. Eli Whitney’s 1793 cotton gin was a particularly famous innovation, commonly credited with having vastly increased cotton’s profitability, fueling an otherwise diminishing demand for slave labor, and so substantially contributing to the American Civil War.3 Variants on Whitney’s gin are known as ‘saw gins’.4 (See Figure 1.) Cotton became more valuable than all other US exports combined during the antebellum era.5 Thus Whitney’s gin is a good contender for representing a discontinuity in innovation.

Our investigation draws heavily from Lakwete’s Inventing the Cotton Gin. Lakwete summarizes the situation surrounding Whitney’s invention as follows6:

The introduction of a new gin in 1794 was as unexpected as it was unprecedented. It was unexpected because the British textile industry had expanded from the sixteenth through the eighteenth centuries without a change in the ginning principle. Cotton producers had increased the acres they planted in cotton and planted new varieties to suit textile makers. The market attracted new producers who, like established planters, used roller gins to process their crops. Roller gins, whether hand-cranked in the Levant and India, or foot-, animal-, and inanimately powered in the Americas, provided adequate amounts of fiber with the qualities that textile makers wanted, namely length and cleanliness. All roller gins removed the fiber by pinching it off in bundles, preserving its length and orientation as grown. Random fragments of fractured seeds were picked out of the fiber before it was bagged and shipped.

In 1788 Joseph Eve gave planters and merchants a machine that bridged the medieval and modern. It preserved the ancient roller principle but completed the appropriation of the ginner’s skill, as Arkwright’s frame had that of the spinner. Appropriation had proceeded in stages beginning with the single-roller gin that mechanized the thumb and finger pinching motion. The roller gin in turn appropriated the agility and strength needed to manipulate the single roller, while the foot gin freed both hands to supply seed cotton. The barrel gin used animal and water power, removing humans as a power source but retaining them as seed cotton suppliers. The self-feeding animal-, wind-, or water-powered Eve gin replaced each of the skilled tasks of the ginner with mechanical components.

Nevertheless, Eli Whitney’s unprecedented gin filled a vacuum. While large merchants invested in barrel gins and large planter in the Eve gin, the majority continued to use the skill- and labor-intensive foot gin to gin fuzzy-seed short-staple cotton as well as the smooth-seed, Sea Island cotton. Barrel gins had not decreased the number of ginners and only marginally improved ginner productivity, and Eve’s complicated gin was notoriously finicky. Whitney ignored these modernizing gins and offered a replacement for the ubiquitous foot gin.

Trends

Pounds of cotton ginned per person-day

We are most interested in metrics that people were working to improve—in this case, perhaps ‘cost of producing a dollar’s worth of cotton’. Inclusive metrics are hard to measure however. Instead we have collected data on ‘pounds of cotton ginned per person per day’, which is simpler, often reported on, and probably a reasonable proxy. However, it departs from tracking the usefulness of a gin by ignoring several major factors:

- Upfront costs: these presumably varied a lot, because a gin can for instance resemble a rolling pin and a board, or involve horses or steam power.8 Thus the gins with higher upfront costs are less useful than their cotton-per-person-day statistic would make them seem. In the mid-1860’s many farms still used foot gins, seemingly because Eve gins—while more efficiently producing high quality output—were expensive.9 Even if everything had the same upfront costs, the existence of upfront costs means that a gin which processes 200lb of cotton with two people per day would be better than one that processes 100lb of cotton with one person, so cotton/person-day still fails to match what we are interested in.

- Variation in labor requirements: Some gins required especially skilled labor.10

- Substitutes for people: some gins used people to power them and others used animals or water-power, along with a smaller number of people.11 This again makes for higher output per person, but at the cost of additional animals, that we are not accounting for.

Risks of injury: Some gins, particularly foot and barrel gins, were dangerous to operate.12

- Types and quality of cotton ginned: Whitney’s gin produced degraded cotton fiber, relative to other gins available at the time.13 However, Whitney’s gin could process short staple cotton, an easier to grow strain which was previously hard to process.14 The cotton industry might adjust to different cotton over time, so that long-run differences in quality of outputs of different gins are smaller than initial differences. If so, we expect value produced by a new gin producing lower quality cotton to grow continuously over an extended period.

We do also investigate overall cost per value of cotton ginned later, but do not have such clear data for it (see section, ‘cost per value of cotton ginned’).

Data

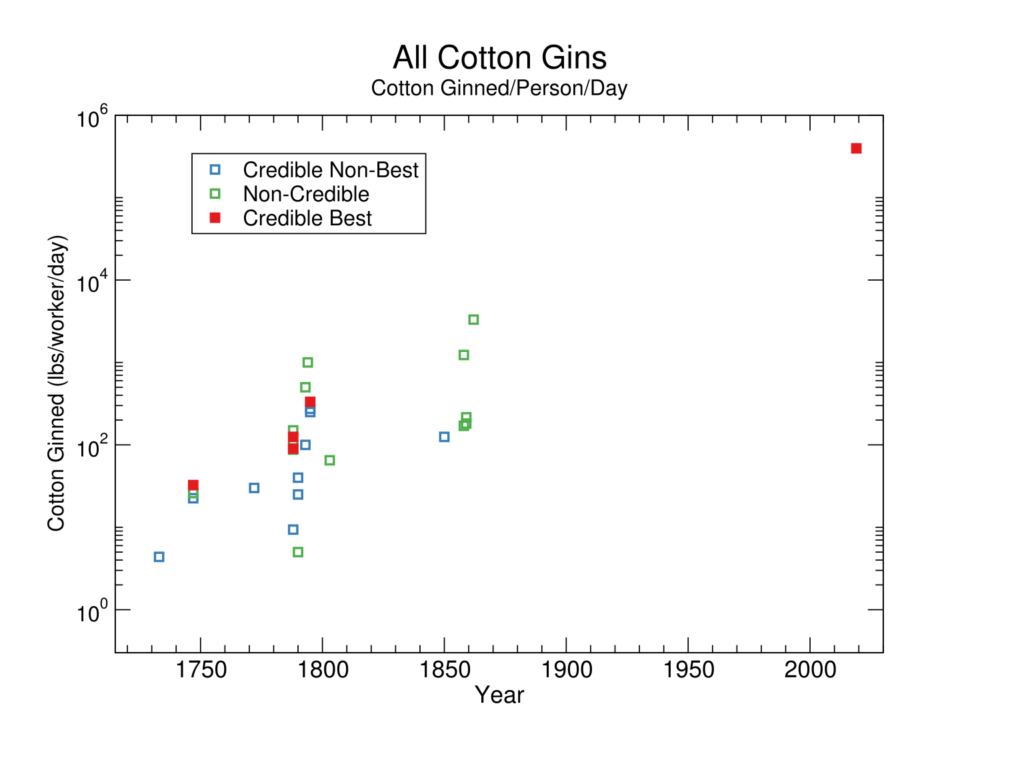

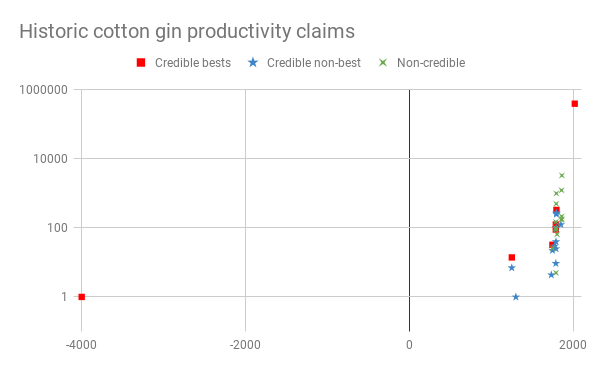

We collected claims about cotton gin productivity in the time leading up to Whitney’s gin, and some after. Many but not all are from Angela Lakwete’s book, Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America.15 Our sources are mostly secondhand or thirdhand claims about nonspecific observations in the 1700s. We have the impression that claims in this space are not very reliable.16 We classified claims as ‘credible’ or not, but this is fairly ambiguous, and we would be unsurprised if some of the ‘credible’ claims turned out to be inaccurate, or the ‘non-credible’ ones were correct.

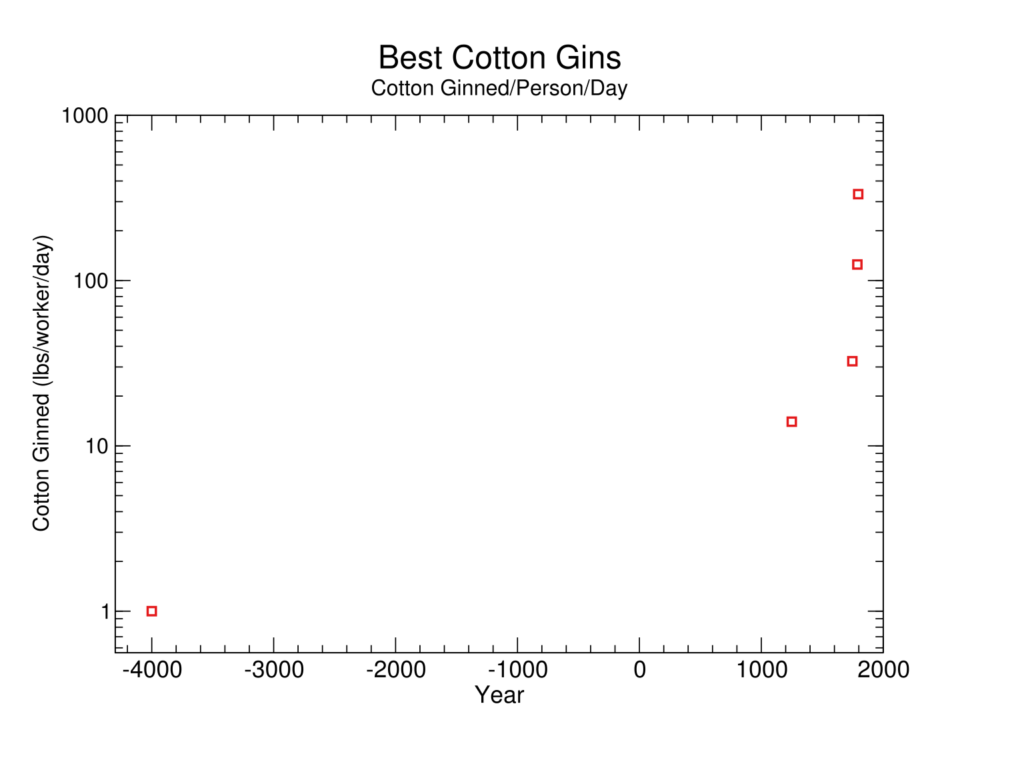

Our dataset of claims is here, and illustrated in Figures 2 – 5. Note that dates are those when a claim was made, not necessarily dates of the invention of the type of cotton gin in question. This is because invention dates are hard to find, and also because it seems likely that much improvement happened incrementally between distinct ‘inventions’ of new types. Nonetheless, this means that a report dated to a time could be from a gin that was built earlier.

Discontinuity measurement

For measuring discontinuities, we treat past progress as exponential at each point, but entering a new exponential regime at the fourth point. We confine our investigation to credible records. Given these things, we find the improved Whitney gin to be a 23-year discontinuity over the previous record in this dataset. However the foot gin and Eve’s mill gin appear to be at least one-thousand year discontinuities each.17.

However our data has at least one key gap. Whitney’s original 1793 gin design was almost immediately copied and improved by many people, most notably Hodgen Holmes and Daniel Clark.18 The plausible productivity data we have appears to all be for these later variants, which we understand were non-negligibly better than Whitney’s original gin in some way.19 So we know that Whitney’s gin should be somewhat lower and two years earlier than our first data for Whitney-style gins. This means at most, Whitney’s original gin would be a 25 year discontinuity. If it accounted for even half of the progress since Eve’s mill gin, and we are not missing further innovations between the two, Whitney’s gin would still represent a 13 year discontinuity, and the later improved version would no longer account for a discontinuity of more than ten years.20 It seems likely to us that Whitney’s gin was at least this revolutionary so we think the Whitney gin probably represented a moderate (10-25 year) discontinuity in pounds of cotton ginned per day.

We are fairly uncertain about whether the two larger discontinuities earlier are real, or due to gaps in our data. We did attempt to collect data for these earlier times (rather than just prior to the Whitney gin), but seem very likely to be missing a lot.

In addition to the size of these discontinuities in years, we have tabulated a number of other potentially relevant metrics here.21

Changes in the rate of progress

Over the history of gin productivity, the average rate of progress became higher. It is unclear whether this happened at a particular point. In our data, it looks as though it happened with the foot gin, in 1747, and that progress went from around .05% per year to around 4% per year (see our spreadsheet, tab ‘credible record gin calculations’). However our data is too sparse and uncertain to draw firm conclusions from.

Cost per value of cotton ginned

As discussed above, pounds of cotton ginned per person-day is not a perfect proxy of the value of a cotton gin, and therefore presumably not exactly what cotton-gin users were aiming for. ‘Cost per value of cotton ginned’ seems closer, if we measure costs inclusively and average across various cotton ginning situations. We did not collect data on this, but can make some inferences about the shape of this trend—and in particular whether Whitney’s gin represented a discontinuity—from what we know about the pounds/person-day figures and other aspects of the situation.

Evidence from the trend in pounds of cotton ginned per person-day

We expect that the pounds of cotton ginned per person-day roughly approximates cost per value of cotton ginned, with the following adjustments that we know of:

- Eve’s gin is worse on cost/value than on cotton/person-day because the latter metric doesn’t reflect its large upfront costs.

- Whitney’s gin may be worse on cost per value than it appears, because of its lower-quality cotton output.

- Whitney’s gin may be better than it appears, because it could handle short-staple cotton. However this value seems unlikely to have manifest immediately, since it presumably takes time for cotton users to adjust to a new material.

- Foot gins and barrel gins (e.g. Eve’s) were dangerous to operate, so are worse on cost/value than they appear.

- Foot gins apparently required especially skilled labor, so are worse on cost/value than they appear.

- Barrel gins and Eve gins often ran on non-human power-sources, so are worse on cost/value than they appear.22

These are several considerations in favor of Whitney’s gin representing more progress on cost/value than on cotton/person-day, and one against. However it is unclear to us whether the downside of lower quality cotton was larger than the other considerations combined, so the overall effect on the expected size of discontinuity from Whitney’s gin seems ambiguous, but probably in favor of larger.

Evidence from takeup of gins

The foot gin persisted for at least sixty years after Whitney’s invention.23 This suggests that Whitney’s gin wasn’t radically better on cost per value of cotton ginned than its predecessors, at least for some cotton producers.

On the other hand, apparently there was a rush to manufacture copies of Whitney’s gin, so much so that many mechanics became professional gin-makers, and most plantations had one of the new gins within five years. 24

This suggests that there were situations for which Whitney’s gin was substantially better than alternatives, and situations for which it was worse. This seems like weak evidence that on average across cotton ginning needs it was not radically better than precursors, though there might be narrower metrics we could define on which it was radically better.

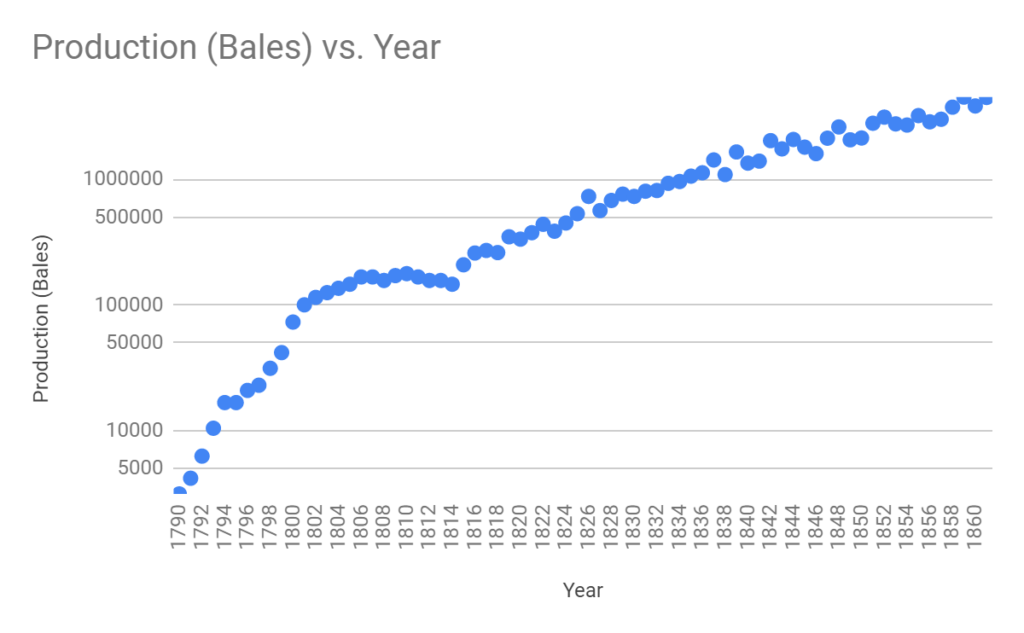

Evidence from cotton production trends

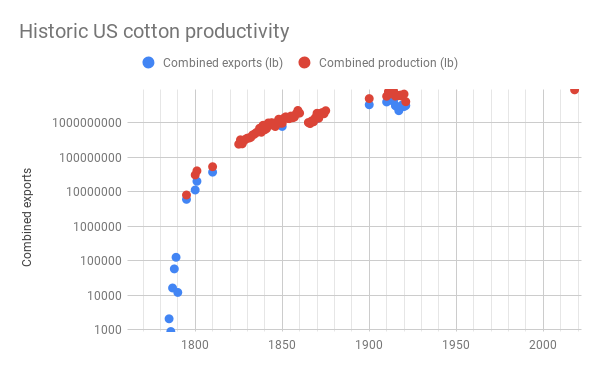

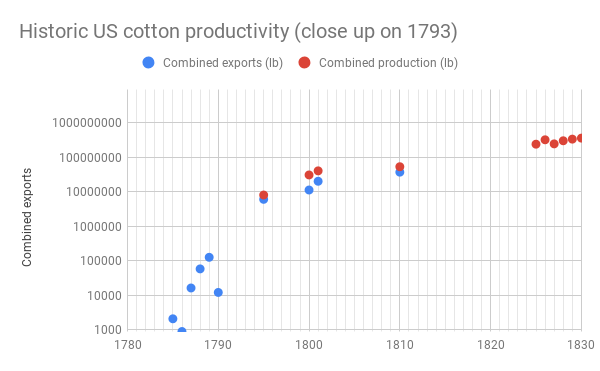

If the Whitney gin made cotton much cheaper to process, we might expect cotton production at the time to sharply increase. Our impression is that this is a common story about what happened.25 However the data we could find on this, seemingly from a 1958 history of early US agriculture, suggests that cotton production was already growing rapidly, and continued on a similar trajectory after Whitney’s invention.26 See Figure 5.

This dataset begins in 1790, only a few years before Whitney’s invention. This is enough to see that the trend just before 1793 is much like the trend just after, however we can further verify this by looking at earlier cotton export figures (Figure 7).27 Cotton exports appear to closely match overall productivity where the trends overlap, and the pre-1790 export trend appears to be roughly continuous with the rest of the curve, at least if we ignore the aberrantly low 1790 figure.

This does not preclude a large change in gin efficacy—perhaps there were other bottlenecks to cotton productivity, or it took time for the gains from Whitney’s gin to manifest in national productivity data. However it does cause us to doubt the story of Whitney’s gin being evidently responsible for massive growth in the cotton industry, which was a reason for suspecting the gin may have represented discontinuous progress. So this is some evidence against Whitney’s gin representing a large discontinuity in cost per value of cotton ginned.

Evidence from the 1879 evaluation of ginning technology

This 1879 evaluation of ginning technology reports on extensive measurement trials of different cotton gins. It was seemingly conducted to understand why Indian cotton production lagged behind American. The author says all methods for ginning cotton in India were primitive until recently; he hears that in some places it was done by hand as late as 1859.29 This is confusing because if Whitney’s gin really was much better in terms of cost-per-value than the alternatives, it would be surprising if sixty years later the alternatives were still in use. However many alternatives seem clearly more cost-effective than ginning by hand, so this seems like little evidence about Whitney’s gin in particular.

The outputs of the gins in the experiment seem different from (and usually higher than) the outputs for similarly named gins in our dataset. Which might be confusing, but we expect is because there are modest improvements to gin technology over time within particular classes of gin.

In sum, this evidence looks as though it might be informative, but we do not see it as such on consideration.

Evidence from historians

We have not thoroughly reviewed popular or academic opinions on the discontinuousness of the cotton gin, but our impression is that a common popular view is that Eli Whitney’s cotton gin was a discontinuous improvement over the state-of-the-art. On the other hand Dr Lakwete, author of Inventing the Cotton Gin—a book we found most helpful in this project, and that also won an award for being the best scholarly book published about the history of technology30—disagrees, actually explicitly saying it was continuous (though she may mean something different by this than we do):

Collapsing two hundred years of cotton production and roller gin use in North America in to the moment when Eli Whitney invented the toothed gin, Phineas Miller and Judge Johnson marked 1794 as a turning point in southern development. Before, southeners languished without an effective gin for short-staple cotton; afterwards, the cotton economy blossomed. Arguing for discontinuity, the idea allowed the visualization of a moment and a machine that separated the colonial past from the new republic. Continuity, however, marked the history of cotton and the gin in America. Continuity would characterize the first two decades of the nineteenth century, as saw-gin and roller gin makers competed for dominance in the expanding short-staple cotton market.

Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. , 71.

Conclusions on cost per value of cotton ginned

On the earlier ‘pounds of cotton ginned per person per day’ metric, we estimated that Whitney’s gin was worth around 10-25 years of past progress. Various considerations suggested Whitney’s gin might have been a bigger deal for overall cost-effectiveness of ginning cotton than that calculation suggested, but the quality of cotton was lower. We took this in total as neutral to weakly favoring Whitney’s gin being better than it seemed. We then saw that the Whitney gin was taken up with enthusiasm by a subset of people needing to gin cotton, that it didn’t seem to recognizably affect the growth of US cotton production, and that at least one historian with particular expertise in this topic thinks that progress was relatively continuous. This does not particularly suggest to us that Whitney’s gin represented a large discontinuity in cost per value of cotton ginned, and seems like some evidence against.

Notes

- “Archaeologists’ oversight may explain the absence of evidence that would locate the single-roller gin in prehistory. That the rollers of extant gins are made of iron does not preclude the possibility that the machine predates the Iron Age. The roller could have been made out of stone…”

Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, 4. - Wikipedia says: “A modern mechanical cotton gin was created by American inventor Eli Whitney in 1793 and patented in 1794…It revolutionized the cotton industry in the United States, but also led to the growth of slavery in the American South as the demand for cotton workers rapidly increased. The invention has thus been identified as an inadvertent contributing factor to the outbreak of the American Civil War.[4] ”

“Cotton Gin.” In Wikipedia, June 4, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cotton_gin&oldid=900249024. - “In 1794 Eli Whitney patented a new ginning principle and built a new kind of gin. Instead of rollers that pinched off the fiber, he used course wire teeth that rotated through a tightly spaced metal grate to pull it from the seed…Industry ambivalence spurred others to adopt the gin but change it. Gin makers substituted an axle loaded with fine-toothed circular saws for Whitney’s wire-studded wooden cylinder. In 1796 Hogden Holmes of Augusta, Georgia, patented the adaptation, naming it the saw gin. The suit that followed capped a contentious and socially and legally mediated process from which Eli Whitney emerged as the inventor of the cotton gin.”

Angela Lakwete, Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America (JHU Press, 2003), 47.

- First table of p567,

Federal Reserve Bulletin (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1923), https://books.google.com/books?id=oNnL2qUnv1AC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

- “Instead of being replaced, the foot gin outlasted the barrel gin and remained in use to the mid-1860s. … The [Eve gin] was labor-saving but capital-intensive. It was more expensive than the foot gin and required water or windmill as well as a reinforced building that could withstand the vibrations of the feeder. Yet it increased outturn without changing the quality of the fiber…” Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003., 40.

- “Foot ginners could be productive… but they were the most valuable men a planter owned or hired. With Eve’s gin, planters used that labor to produce cotton and “only the most ordinary” workers to gin it.” Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003., 45.

- “The [Eve gin] was labor-saving but capital-intensive. It was more expensive than the foot gin and required water or windmill …” Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003., 40.

“McCarthy’s gin was adopted for cleaning the Sea Island variety of extra-long staple cotton grown in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. It cleaned cotton several times faster than the older gins, and, when powered by one horse, produced 150 to 200 pounds of lint a day.”

“Cotton Gin,” in Wikipedia, June 4, 2019, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Cotton_gin&oldid=900249024.

- “The oxen and water-driven barrel gins that Drayton described could not be stopped quickly, so ginners risked serious injury.”…”Foot gins were not without their own risks and limitations.” Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003., 39.

- “In 1794 Eli Whitney patented a new ginning principle and built a new kind gin…It turned out large quantities of fiber but destroyed the very qualities that textile makers had valued.”

Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, 47

“But textile makers continued to complain about the quality of the fiber the toothed gin turned out.” Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003., 63

- “In the colonial era, small amounts high quality long-staple cotton were produced in the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina. Inland, only short-staple cotton could be grown but it was full of seeds and very hard to process into fiber. The invention of the cotton gin in the late 1790s for the first time made short-staple cotton usable.”

“History of Agriculture in the United States.” Wikipedia. April 11, 2019. Accessed April 25, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_agriculture_in_the_United_States#Cotton.

“The Indian roller cotton gin, known as the churka or charkha, was introduced to the United States in the mid-18th century, when it was adopted in the southern United States. The device was adopted for cleaning long-staple cotton, but was not suitable for the short-staple cotton that was more common in certain states such as Georgia. Several modifications were made to the Indian roller gin by Mr. Krebs in 1772 and Joseph Eve in 1788, but their uses remained limited to the long-staple variety, up until Eli Whitney’s development of a short-staple cotton gin in 1793″

“Cotton Gin.” Wikipedia. April 03, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cotton_gin.

- For instance, some claim Barclay was a slave, another elaborates his story as a plantation owner. Data from here suggests a large drop in cotton bale production between 1860 and 1880, yet this says, “By 1870, sharecroppers, small farmers, and plantation owners in the American south had produced more cotton than they had in 1860, and by 1880, they exported more cotton than they had in 1860.” Most of all, Whitney’s own claim about the productivity of his original gin is arguably too outlandish to be believed—while estimates of gin productivity slightly later don’t reach 400lbs/person-day (see our data below), Whitney apparently claimed his gin could produce 1250lb/person-day:

“Two ginners on the new gin could turn out as much fiber in a day as one hundred foot ginners each averaging twenty-five pounds, in all twenty-five hundred pounds, Whitney estimated.” (Whitney quote from Angela Lakwete, Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America (JHU Press, 2003), p49)

- See our methodology page page for more details, and our spreadsheet, tab ‘credible record gin calculations’ for our calculations.

- “Mississippi’s first saw gin was constructed in violation of Whitney’s patent rights during the summer of 1795 and put into operation in September. Daniel Clark, Sr., a wealthy planter of Wilkinson County, designed this famous machine after examining drawings made by a traveler who had seen one of Whitney’s gins while on a trip to Georgia.”

Moore, John Hebron. Agriculture in Ante-Bellum Mississippi. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2010, page 21.

In 1796 Hogden Holmes of Augusta, Georgia, patented the adaptation, naming it the saw gin. The suit that followed capped a contentious and socially and legally mediated process from which Eli Whitney emerged as the inventor of the cotton gin.

Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, p47 - We do have Whitney’s own estimate of his gin’s productivity, but since it is very much larger than estimates of later related gins (see our data), we assume it is an exaggeration:

“Two ginners on the new gin could turn out as much fiber in a day as one hundred foot ginners each averaging twenty-five pounds, in all twenty-five hundred pounds, Whitney estimated.”

Angela Lakwete, Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America (JHU Press, 2003), p49 - See our methodology page for more details.

- “The barrel gin used animal and water power, removing humans as a power source but retaining them as seed cotton suppliers. The self-feeding animal-, wind-, or water-powered Eve gin replaced each of the skilled tasks of the inner with mechanical components.” Lakwete, Angela. Inventing the Cotton Gin: Machine and Myth in Antebellum America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003, p48

- “Because the demand for saw gins became very great during the next few years a number of local mechanics embarked upon careers as professional ginwrights. … By [1800] one [of the new gins] could be found on almost every plantation.” Moore, John Hebron. Agriculture in Ante-Bellum Mississippi. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 2010

- For instance, History.com:

“In 1794, U.S.-born inventor Eli Whitney (1765-1825) patented the cotton gin, a machine that revolutionized the production of cotton by greatly speeding up the process of removing seeds from cotton fiber. By the mid-19th century, cotton had become America’s leading export. Despite its success, the gin made little money for Whitney due to patent-infringement issues. Also, his invention offered Southern planters a justification to maintain and expand slavery even as a growing number of Americans supported its abolition. “

History com Editors, “Cotton Gin and Eli Whitney,” HISTORY, accessed June 18, 2019, https://www.history.com/topics/inventions/cotton-gin-and-eli-whitney. - This spreadsheet of ours contains data from this image, which appears to be taken from History of Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860, Volume 2, given that the author is the same and it is from the same page in the book. The full citation is:

Gray, Lewis Cecil, and Esther Katherine Thompson. History of Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860. Peter Smith, 1958. - We made a rough collection of export and production data from numerous sources. See here. We have not vetted these, and the collection process was not thorough or reliable. However since the figures are fairly consistent, we expect that they are roughly correct.

- “How primitive, till comparatively a few years since, were the means of cleaning the ‘kuppas’ or seed cotton is best shown by the fact that in the accounts of even 20 years ago repeated mention is made in some districts of picking the wool off the seed by hand…” Watson, Forbes. Report on cotton gins and on the cleaning and quality of Indian cotton. London, Allen, 1879.

- “Inventing the Cotton Gin won the 2004 Edelstein Prize given by the Society for the History of Technology for the best scholarly book published about the history of technology in the past three years.”

“Angela Lakwete – Department of History – College of Liberal Arts – Auburn University.” Accessed October 27, 2019. https://cla.auburn.edu/history/people/emeritus/angela-lakwete/.