Table of Contents

Historic trends in book production

Published 07 February, 2020; last updated 28 May, 2020

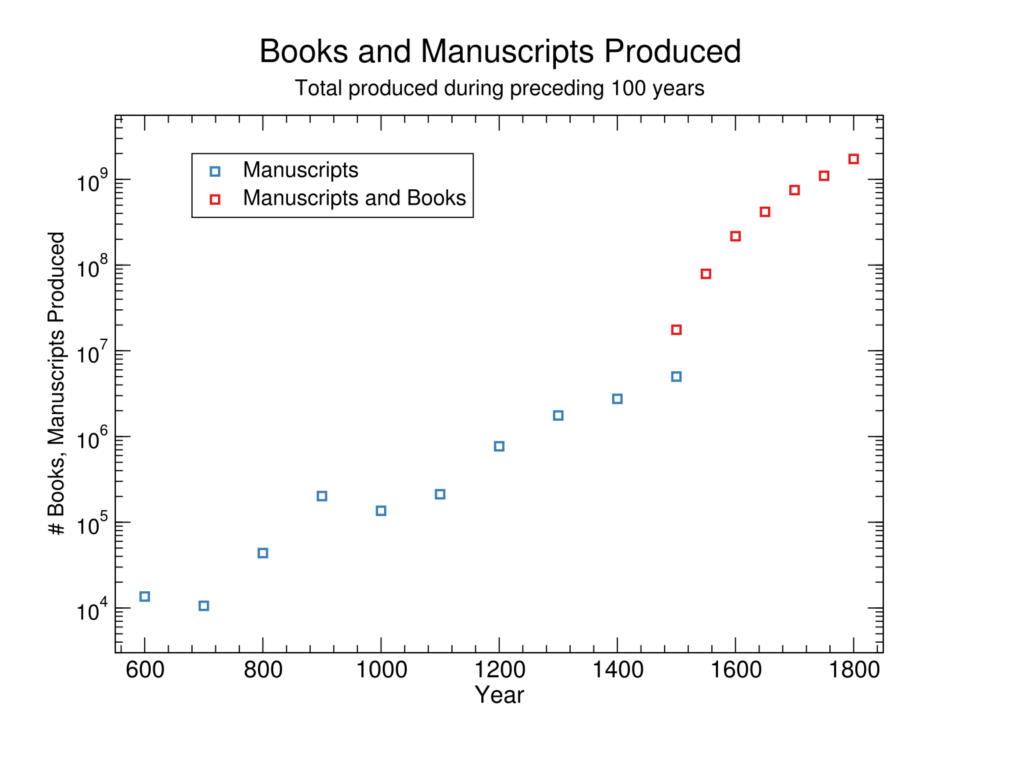

The number of books produced in the previous hundred years, sampled every hundred or fifty years between 600AD to 1800AD contains five greater than 10-year discontinuities, four of them greater than 100 years. The last two follow the invention of the printing press in 1492.

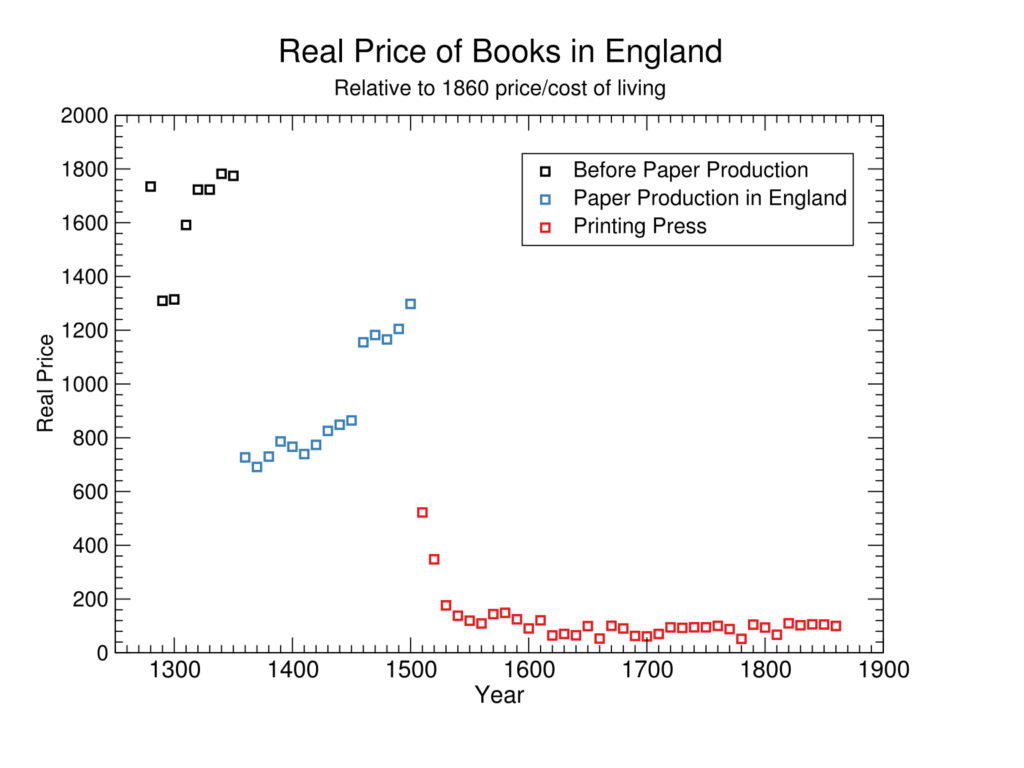

The real price of books dropped precipitously following the invention of the printing press, but the longer term trend is sufficiently ambiguous that this may not represent a substantial discontinuity.

The rate of progress of book production changed shortly after the invention of the printing press, from a doubling time of 104 years to 43 years.

Details

This case study is part of AI Impacts’ discontinuous progress investigation.

Background

Around 1439, Johannes Gutenburg invented a machine for making books commonly referred to as “the printing press”. The printing press was used to quickly copy pre-created sheets of letters of ink onto a print medium.1 Presses that stamped paper with carved blocks of wood covered in ink were already being used in Europe,2 but Gutenburg made several major improvements on existing methods, notably creating the hand mould, a device which allowed for quickly creating sheets of inked letters rather than carving them out of wood. The printing press allowed for the quick and cheap production of printed books like never before.3

Trends

We looked primarily at two different metrics– the rate of book production in Western Europe and the real price of books in England. We chose these two because they were some of the only printing-related data sources which had data that went back several centuries before the invention of the printing press.

Had the data been available, we would like to have looked at some metric correlated clearly with innovations in the writing / printing process — e.g. the number of pages produced per worker per hour. Then we could check whether the printing press represented a discontinuity relative to earlier innovations (e.g., the pecia system for hand-copying manuscripts).5

Unfortunately, neither the rate of book production nor the price of book data we have correlate well with innovations in the writing / printing process. The authors of our rate of book production data claim that most of the variation in the pre-printing press numbers is explained by factors which are not innovation or close proxies to innovation.6 Our data on the price of books is similarly unhelpful, as the early price data is too sparse to be meaningful.

In addition to the two metrics described above, we looked cursorily at a few metrics with no early data which changed drastically as a result of the printing press– the number of unique titles printed per year, the variation of genres in books, the price of books in the Netherlands, and the total consumption of books.

Rate of book production in Western Europe

Data collection

Our data for the rate of book production come from estimates of Europe-only production generated in a 2009 paper by historians Eltjo Buringh and Jan Luiten Van Zanden.7 Rate data is represented as the number of books produced in the previous 100 years at various points in time.

When we use the term book, we mean it to refer to any copy of a written work, whether hand-copied manually or produced via some kind of printing technique. The paper separates book production into estimates of manuscript and printed book production, where the production of printed books starts only after the printing press is invented. We will also use the terms manuscript and printed book to talk about the data, but it’s unclear to us if the paper means manuscript to mean “any book not made using a Gutenburg-era printing press” or “any book transcribed by hand”. At one point the authors sum these two estimates into a single graph of production per capita,8 suggesting that the combination of manuscript and printed book data should cover all books.

The paper’s estimates for manuscript production are constructed by taking an existing sample of manuscripts and then attempting to correct for its geographical and temporal biases.9 Estimates for book production are constructed by counting new titles in library catalogues and multiplying by estimates for average prints per title at a given time.10

The estimates of manuscript production seem extremely non-robust given that large number of correction factors applied.11 The estimates of book production seem somewhat more robust, but should be taken as a lower bound as the authors did not correct for lost books and have estimated the average number of prints per title conservatively.12

Data

Figure 1a displays the raw data for rate of book production on a log scale, taken from the data in the paper described above and compiled in this spreadsheet. Each data point represents the total number of books produced in the previous 100 years.

Figure 1b displays the same data as Figure 1a along with our interpretation.

Looking at the data, we assume an exponential trend up until 1500, and another one after that.13 The blue line is the average log rate of the rate of book production before the invention of the printing press (just manuscripts); the red line is the average log rate of the rate of book production after the invention of the printing press (manuscripts + printed books).

Grey points shown after 1500 reflect projected manuscript and therefore book production had the printing press not been invented. In practice, the actual number of manuscripts produced after 1500 were very small and not presented in the data.

Discontinuity measurement

If we just look at the trend of book production per past 100 years, measured once every 100 years before 1500, and then once every 50 years afterwards, we can calculate discontinuities of sizes 161 years in 900, 134 years in 1200, 23 years in 1300, 180 years in 1500, and 138 years in 1550.14 This is obviously a strange kind of trend–a discontinuity of one hundred years in a metric with datapoints every hundred years might mean nothing perceptible at the one-year scale. So in particular, these discontinuities do not tell us much about whether there would be discontinuities in a more natural metric, such as annual book production.

Changes in the speed of progress

There was a marked change in progress in the rate of book production with the invention of the printing press, corresponding to a change in the doubling time of the rate of book production from 104 years to 43 years.15

Interpreting this rate of change on the graph, before the invention of the printing press, the total rate of book production, which consists entirely of manuscripts, follows the exponential line shown in blue. The invention of the printing press in 1439 allows for mass production of printed books, causing the rate of book production to veer sharply off the existing exponential line, shown as the first point in red. Note that our underlying data sources are non-robust, particularly for manuscript data pre-printing press, so the magnitude of this change in rate of progress may be under or overstated.

Discussion of causes

The change in the doubling time of the rate of book production caused by the printing press may reflect a large change in the factors that drove book production.

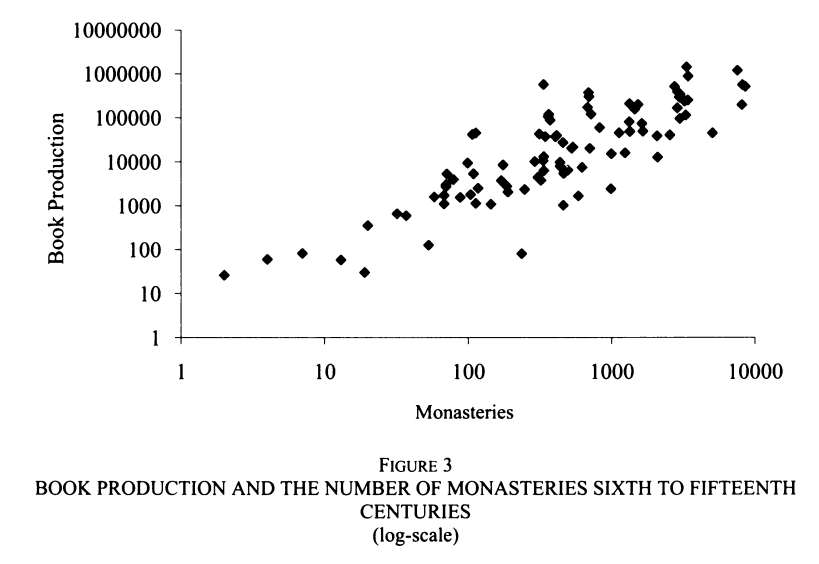

In their paper, Buringh and Van Zanden note that in the Middle Ages, 60% of the variation in book production is explained by the number of universities, the number of monasteries, and urbanization.16 They produce the following graph, correlating monastery numbers and early book production:

By contrast, after the printing press was invented, Buringh and Van Zanden attribute a much more important role to individual book consumption and the forces of the market:

How to explain the significant increase in book production and consumption in the centuries following the invention of moveable type printing in the 1450s? The effect of the new technology (and import technological changes in the production of paper) was that from the 1470s on, book prices declined very rapidly. This had number of effects: consumption per literate individual increased, but it also became more desirable and less costly to become literate. Moreover, economies of scale in the printing industry led to further price reductions stimulating even more growth in book consumption.

It seems plausible that the move between exponential curves caused by the printing press was a shift from an exponential curve that reflected the growth of monasteries, universities, and cities to an exponential curve that reflected the growth of a complicated set of market forces.

Real price of books in England

Data collection

We took data from a 2004 paper written by economic historian Gregory Clark, who took data from historic records of price quotes,17 though data before 1450 is based on just 32 total price quotes, and Clark notes that “the prices vary a lot by decade since it is hard to control for the quality and size of the manuscript.”18 As such, we should not take much meaning out of the individual data points before 1450 or interpret the period between 1360 and 1500 as a rising trend.

Clark’s paper reports an index of the nominal price of books in Table 9 of his paper. To instead get an index of the real price of books,19 we divided each nominal price by Clark’s reported “cost of living” for each year (x 100), which was the amount of money paid by a relatively prosperous consumer for the same bundle of goods every year.20

Data

Figure 3 is a graph of (an index of) the real price of books in England, generated from the data described above and compiled in this spreadsheet. Each point represents the amount of money in each year needed to buy some bundle of books assuming you would pay 100 for that same bundle of books in 1860.

Economist Timothy Irwin, looking at this same dataset, claims that the drop in price around 1350 was due to knowledge about paper-making finally making its way to England: “As time passed, improvements in technology and the gradual spread of literacy reduced these obstacles to effective transparency. In particular, the diffusion of knowledge about paper-making (from around 1150) and then printing (from around 1450) dramatically reduced the price of books. (See Figure 1 for an estimate of the decline in England).”21

‘Figure 1’ in the quote above refers to a graph of the real price of books that uses the same data source and is identical to the one we generated. His claim seems plausible, but we are not confident about it given how sparse and noisy the early data is and given our lack of precise date information on how paper-making spread in England.

Discontinuity measurement

The graph contains two major drops– one as a result of the printing press, and one claimed to be the result of paper replacing parchment in England. Looking at just the set of blue data points between these two drops, we can see that they are clustered around some range of values. The data in this range is too noisy and sparse22 to generate a meaningful rate of progress, but it seems clear that for a wide variety of plausible rates, the printing press represented a discontinuity in the real price of books when compared to the trend in book prices after the spread of paper-making.

However, if you take the past trend to include the price of books before paper-making, then there is no clear discontinuity– the price of printed books could be part of an existing trend of dropping prices that started with paper-making. We also believe the data here is too poor to draw firm conclusions.

Discussion of causes

Whether or not it counts as a substantial discontinuity relative to the longer term trend, the printing press produced a sharp drop in the real price of books. This was because their price was largely driven by labor costs, which went down sharply (one author estimates by a factor of 341) when a laborer could use a machine to print massive numbers of books rather than manually transcribing each copy.23

Other noteworthy metrics

Many historians associate the invention of the printing press with other unsurprising book-related changes in the world, including:24

- An increase in the productivity of book production, i.e. the ratio between the wage of a copy producer and the price of a standard book. In particular, one estimate measures a 20-fold increase in the productivity in the first 200 years after the invention.25 Another estimate guesses that there was a 340-fold decrease in the cost per book as a direct result of the printing press.26

- A sharp decrease in the real price of books. One estimate of the real price of books in the Netherlands suggests a ~5-fold decrease between 1460 and 1550.27

- An increase in genre-variety of books, and in particular a shift away from theological texts and an increase in the amount of fiction.28

- An increase in the total consumption of books, likely as a result of their declining price and increased literacy levels.29

Most of these changes are gradual over at least a century, rather than involving a sharp change that might be a large discontinuity. Such gradual changes might suggest a sharper change in some underlying technology though, for instance. The fall in the price of Dutch books was relatively abrupt, but the data lacks a trend leading up to the printing press.

The increases in the number of genres and unique titles published suggest that there was a larger amount of information available in printed form. Decreased prices and increased consumption of books suggests that this information was easier to access than before. These things suggest there might have been an interesting change in availability of information in general, however we do not know enough about the past trend to say whether this was likely to be discontinuous.

Notes

- “Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (/ˈɡuːtənbɜːrɡ/;[1] c. 1400 – February 3, 1468) was a German blacksmith, goldsmith, inventor, printer, and publisher who introduced printing to Europe with the printing press. […] Gutenberg in 1439 was the first European to use movable type. Among his many contributions to printing are: the invention of a process for mass-producing movable type; the use of oil-based ink for printing books; adjustable molds; mechanical movable type; and the use of a wooden printing press similar to the agricultural screw presses of the period. His truly epochal invention was the combination of these elements into a practical system that allowed the mass production of printed books and was economically viable for printers and readers alike.” – “Johannes Gutenberg”. 2018. En.Wikipedia.Org. Accessed May 28 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Johannes_Gutenberg&oldid=895246592

- “Printing in East Asia had been prevalent since the Tang dynasty, and in Europe, woodblock printing based on existing screw presses was common by the 14th century.” – “Printing Press”. 2015. En.Wikipedia.Org. Accessed June 3 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Printing_press&oldid=899397867

- “Gutenberg’s most important innovation was the development of hand-molded metal printing matrices, thus producing a movable type-based printing press system. His newly devised hand mould made possible the precise and rapid creation of metal movable type in large quantities. Movable type had been hitherto unknown in Europe. In Europe, the two inventions, the hand mould and the printing press, together drastically reduced the cost of printing books and other documents, particularly in short print runs.” – “Printing Press”. 2015. En.Wikipedia.Org. Accessed June 3 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Printing_press&oldid=899397867

- “Moreover, thanks to other innovations in the high Middle Ages (in particular, the substitution of paper for parchment, but also the spread of more efficient ways of hand copying manuscripts, such as the pecia system) and the fifteenth century (the printing press), the price of books was greatly reduced, providing additional impulse to the growth process.” – Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. “Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries.” The Journal of Economic History69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837, 425.

- “If we take the Middle Ages as a whole, the three factors we have data for– universities, monasteries, and urbanization– together explain almost 60 percent of the variation in per capita book production (first two columns).” – Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. “Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries.” The Journal of Economic History 69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837, 431.

- Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. “Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries.” The Journal of Economic History 69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837

- See Figure 2 in this paper which sources data from manuscript and printed book estimates in Tables 3 and 4. – Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. “Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries.” The Journal of Economic History 69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837

- “As a result of these four inclusion criteria we may expect temporal and spatial skewness to arise in the global database as a consequence of unavoidable publication and selection biases. Nevertheless, numerically such skewness can be overcome by specific correction and standardization steps, as we will demonstrate later.” Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A long-term perspective from the sixth through eighteenth centuries, Appendix I The Journal of Economic History69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837.

- “We estimate the number of titles or editions that appeared in Western Europe between 1454 and 1800, multiplied by rather crude (and probably relatively low) estimates of the average size of print runs … The most important sources for counting new titles are library catalogues and national and international datasets which are based on these catalogues and present inventories of editions published in different countries and/or languages (the ‘short title catalogues’), most of which are available on-line.”

From Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A long-term perspective from the sixth through eighteenth centuries, Appendix II The Journal of Economic History69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837. - See tables I-3 through I-6 of Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A long-term perspective from the sixth through eighteenth centuries, Appendix I The Journal of Economic History69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837.

- “For a number of reasons our figures should be interpreted as lower-bound estimates: we do not correct for the (many?) books of which all traces have been lost, nor for the fact that at the book fairs only part of the production was presented. Series publications are not included either. The estimates of print runs are also conservative: we follow the literature that average sizes of editions between the 1450s and 1500 probably increased from 100 to 500 (the print run of the Gutenberg bible was 200); there is ample evidence that this increase continued after 500, but at a slower pace. We tentatively estimate that it went up to 1,000 in 1800, again a quite conservative estimate (print runs of mass produced books, such as bibles, prayer books and primary school books increased to more than hundred thousand in some cases).”

From Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A long-term perspective from the sixth through eighteenth centuries, Appendix II The Journal of Economic History69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837. - See our methodology page for more details.

- See our methodology page for more details, and our spreadsheet for our calculation.

In addition to the sizes of these discontinuities in years, we have tabulated a number of other potentially relevant metrics here. See our methodology page for more details. - See our methodology page for more details, and the relevant cells in this spreadsheet for the calculations.

Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. “Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries.” The Journal of Economic History 69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837 “If we take the Middle Ages as a whole, the three factors we have data for– universities, monasteries, and urbanization– together explain almost 60 percent of the variation in per capita book production (first two columns).”- “The price history of pre-industrial England is uniquely well documented. England achieved substantial political stability by 1066. There was little of the internal strife that proved so destructive of documentary history in other countries. Also England’s island position and relative military success protected it from foreign invasion, except for the depredations of the Scots in the border counties. England further witnessed the early development of markets and monetary exchange. In particular when reports of private purchases begin in 1208-9 the markets for goods were clearly well established. A large number of documents with such prices survive in the records of churches, monasteries, colleges, charities, and government.” From

Clark, Gregory. “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous: Living Costs of the Rich versus the Poor in England, 1209-1869.” 2004. MS, UC Davis, Davis. http://www.iisg.nl/hpw/papers/clark.pdf. - “Unfortunately observations on book prices before 1450 are limited: I found only 32 price quotes for these years. And the prices vary a lot by decade since it is hard to control for the quality and size of the manuscript. Even though the scale goes up to 4000%, many of the decadal averages of prices before 1450 cannot be shown.” From

Clark, Gregory. “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous: Living Costs of the Rich versus the Poor in England, 1209-1869.” 2004. MS, UC Davis, Davis. http://www.iisg.nl/hpw/papers/clark.pdf. - We prefer real prices rather than nominal ones because we want to exclude the effects of inflation in our data. See here for a fuller explanation.

- See this spreadsheet for the adjustment calculation. This data with this adjustment was originally made and charted by Timothy C. Irwin: Irwin, Timothy. (2013). Shining a Light on the Mysteries of State: The Origins of Fiscal Transparency in Western Europe. IMF Working Papers. 13. 1. 10.5089/9781475570946.001.

- Irwin, Timothy. (2013). Shining a Light on the Mysteries of State: The Origins of Fiscal Transparency in Western Europe. IMF Working Papers. 13. 1. 10.5089/9781475570946.001.

- See Data collection above.

- “The increased demand of books was driven by a huge decrease in the price of books. The smaller price was possible by the increased efficiency in the production of books since the invention of the printing press around 1440. Clark (2008) measures the subsequent productivity increase as the ratio between the wage of building craftsmen and the price of a book and finds a 20-fold increase in productivity in the first 200 years after the invention, […] Productivity is measured as the ratio between the wage of building craftsmen and the price of a book of standard characteristics. Clark notes that ‘with both hand production and the printing press the main cost in book production was labor (paper and parchment production costs were mainly labor costs).’ Clark (2008) notes that copyists before the time of the printing press were able to copy 3,000 words of plain text per day. This implies that the production of one copy of the Bible meant 136 days of work. Eisenstein5 is able to compare the price of paying a scribe to duplicating a translation of Plato’s Dialogues with the price for duplicating the same work by the Ripoli printing press in Florence in 1483. For three florins the Ripoli Press produced 1,025 copies whereas the scribe would produce one copy for one florin. This implies that the cost per book decreased 341 times with the introduction of the printing press.”

Roser, Max. “Books.” Our World in Data. March 05, 2013. Accessed June 28, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/books#the-publication-of-unique-booktitles-over-the-long-run. - The following points and summary all come from Our World in Data — Books, but they reference a variety of outside data sources. Roser, Max. “Books.” Our World in Data. March 05, 2013. Accessed June 28, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/books#the-publication-of-unique-booktitles-over-the-long-run.

- See this graph, Productivity in book production in England, 1470s-1960s – Clark (2008) originally found in Clark, Gregory. A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World. Vancouver: Crane Library at the University of British Columbia, 2010. , republished in Roser, Max. “Books.” Our World in Data. March 05, 2013. Accessed June 28, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/books#the-publication-of-unique-booktitles-over-the-long-run.

- “In 1483, the Ripoli Press charged three florins per quinterno for setting up and printing Ficino’s translation of Plato’s Dialogues. A scribe might have charged one florin per quinterno for duplicating the same work. The Ripoli Press produced 1,025 copies; the scribe would have turned out one.” Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change Communications and Cultural Transformations in Early-modern Europe ; Volumes I and II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. As Max Roser writes,“Eisenstein is able to compare the price of paying a scribe to duplicating a translation of Plato’s Dialogues with the price for duplicating the same work by the Ripoli printing press in Florence in 1483. For three florins the Ripoli Press produced 1,025 copies whereas the scribe would produce one copy for one florin. This implies that the cost per book decreased 341 times with the introduction of the printing press.” As Max Roser’s summary suggests, 1025 copies / 3 florins per quinterno vs. 1 copy / 1 copy per quinterno is a 341-fold reduction in the cost.

Roser, Max. “Books.” Our World in Data. March 05, 2013. Accessed June 28, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/books#the-publication-of-unique-booktitles-over-the-long-run. - See this graph, Estimates of the real price of Dutch books, 1460-1800 (1460/74 = 100) – van Zanden (2009) with data originally found in Van Zanden, J. L. The Long Road to the Industrial Revolution: The European Economy in a Global Perspective, 1000-1800. Leiden: Brill, 2012. and republished in Our World in Data — Books. The graph shows an average price of ~between 100 and 120 in the 1460s and 70s moving down to an average price of around 20 by 1485, an approximately ~5-fold decrease in price.

Roser, Max. “Books.” Our World in Data. March 05, 2013. Accessed June 28, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/books#prices-of-books-productivity-in-book-production. - “Another fundamental change in the book market after the invention of the book press was a very strong increase in the variety of printed books available to the readers. Dittmar (2012) measures the subject content by employing techniques from machine learning to identify the topics of books in his sample of English books between the late 1400s and 1700. He can thereby identify a specified number of topics in his sample and track the changes in variety over time. He depicts the increased consumer choice by calculating the Herfindahl index of topic concentration – this is reprinted in Panel A of the figure below. Panel B shows how the number of effective variety of consumer choices grew sharply after 1500. The increasing variety represents the end of the dominating role of theological texts – Dittmar (2012) notes that ‘almost all books were on religious topics in the late 1400s […] The following pie chart gives an overview of the variety of book topics in London’s book market in 1700. Looking at the variety of books at that time – the end of Dittmar’s sample – makes one realize how dominant theological texts were before. The data source for this figure is the English Short Title Catalog or ESTC which is also one of the two sources of Dittmar. […] A subsequent change in the variety of topics was the rise of fiction literature. This marked change between the 17th and the 18th century is depicted below. From the table above we know that the total number of books published during this time did not change – in the 50 years before 1700 89,306,000 books were published in Great Britain; in the 50 years after 1700 it was 89,259,000.” From the “Increasing variation of genres and the rise of fiction literature” section in Roser, Max. “Books.” Our World in Data. March 05, 2013. Accessed June 28, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/books#the-publication-of-unique-booktitles-over-the-long-run, referencing Dittmar, Jeremiah. “The Welfare Impact of a New Good: The Printed Book.” Unpublished draft. May 27, 2011. Accessed June 28, 2019.Dittmar (2012) – “The Welfare Impact of a New Good: The Printed Book” (2012).

- See graph from Our World in Data — Books, “Consumption of Books” to see the sudden increase.

Roser, Max. “Books.” Our World in Data. March 05, 2013. Accessed June 28, 2019. https://ourworldindata.org/books#the-publication-of-unique-booktitles-over-the-long-run Roser notes that “The declining price of books and the increasing literacy led to an increase in the consumption of books, as can be seen in the following table.” The data used to produce this graph comes from estimates from Buringh and Van Zanden, who also produced the original estimates for manuscript and book production per century. We would guess that they are not particularly robust, but are likely robust enough to support the marked increase in book consumption.

Buringh, Eltjo, and Jan Luiten Van Zanden. “Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries.” The Journal of Economic History 69, no. 02 (2009): 409. doi:10.1017/s0022050709000837