Table of Contents

Progress in general purpose factoring

Published 16 March, 2017; last updated 07 October, 2017

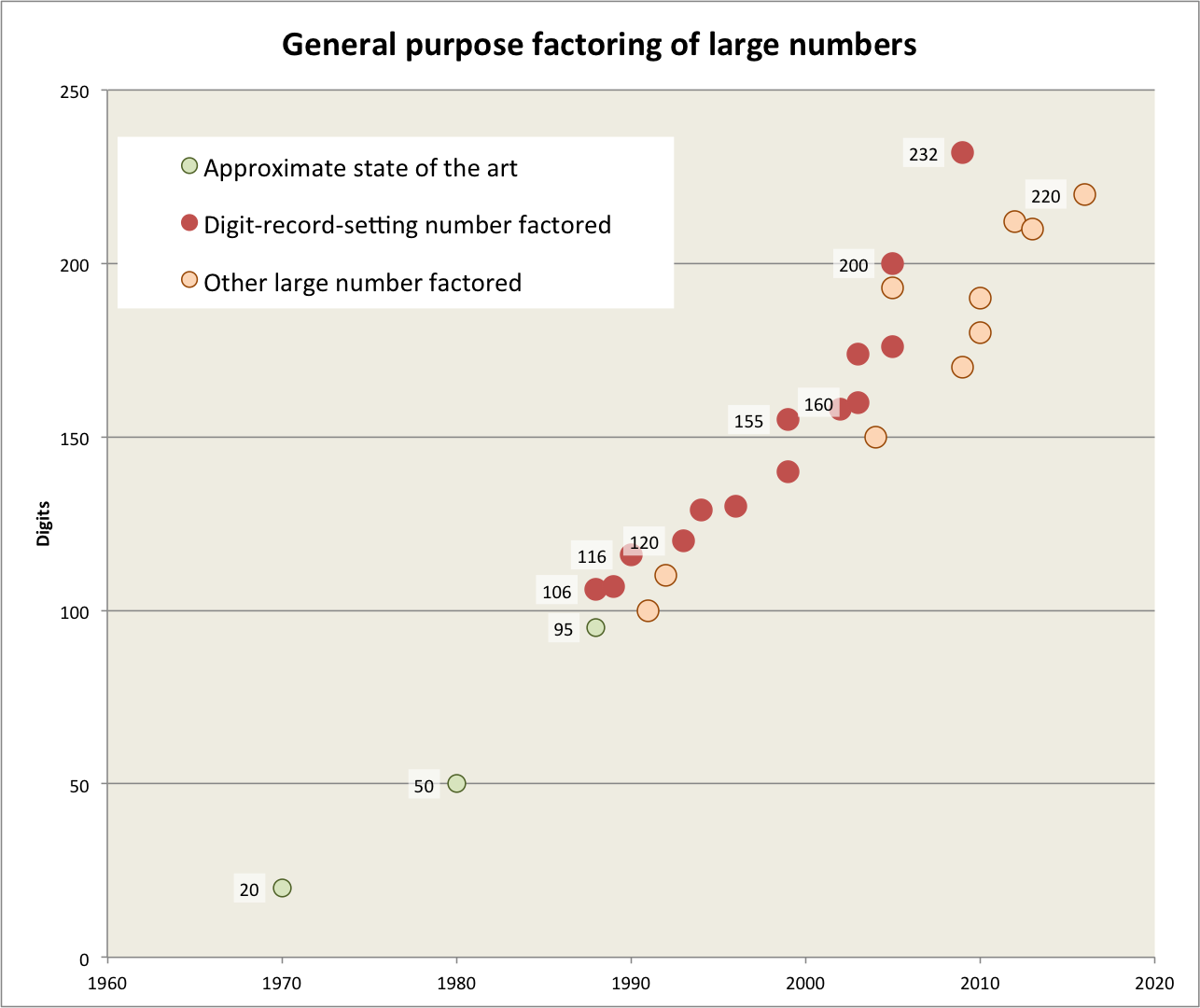

The largest number factored to date grew by about 4.5 decimal digits per year over the past roughly half-century. Between 1988, when we first have good records, and 2009, when the largest number to date was factored, progress was roughly 6 decimal digits per year.

Progress was relatively smooth during the two decades for which we have good records, with half of new records being less than two years after the previous record, and the biggest advances between two records representing about five years of prior average progress.

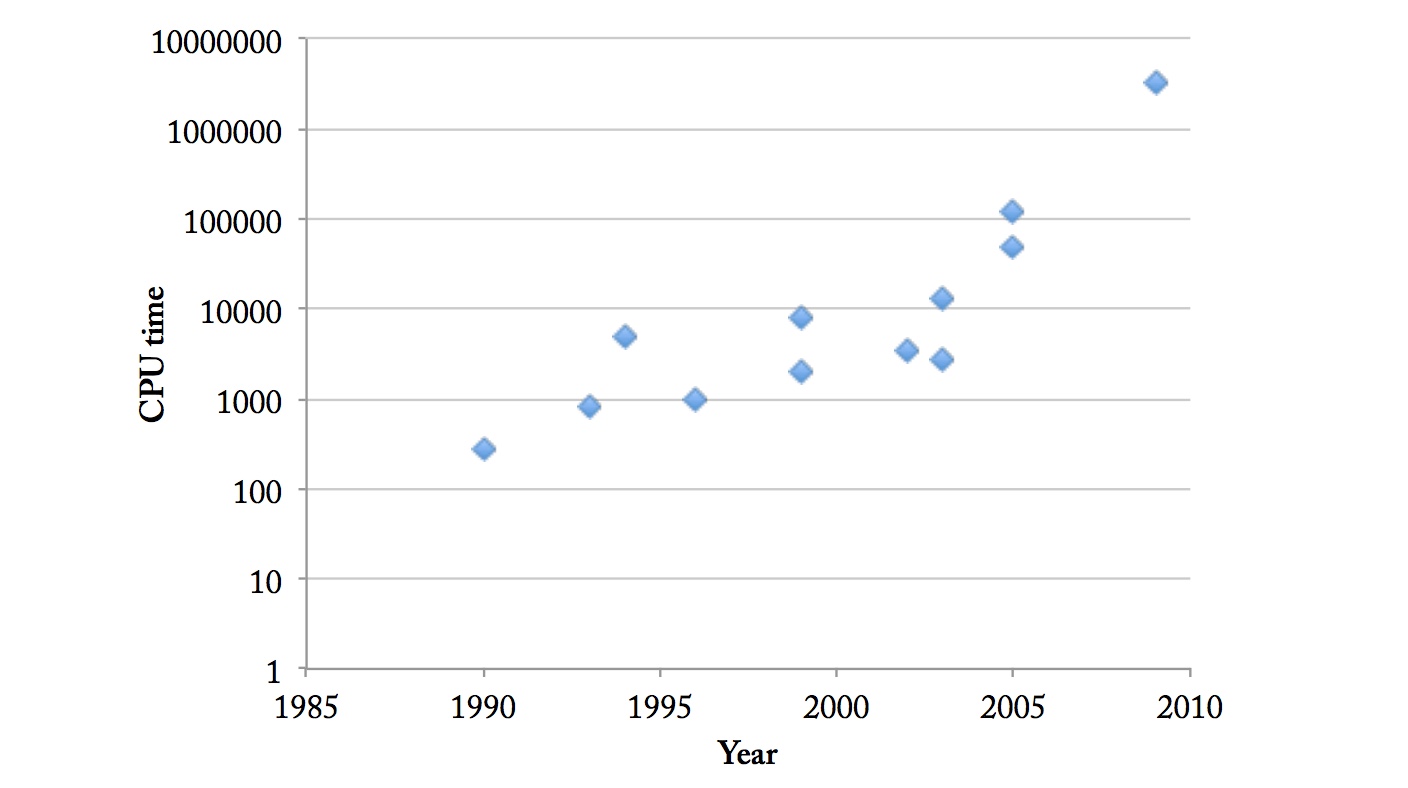

Computing hardware used in record-setting factorings increased ten-thousand-fold over the records (roughly in line with falling computing prices), and we are unsure how much of overall factoring progress is due to this.

Support

Background

To factor an integer N is to find two integers l and m such that l*m = N. There is no known efficient algorithm for the general case of this problem. While there are special purpose algorithms for some kinds of numbers with particular forms, here we are interested in ‘general purpose‘ factoring algorithms. These factor any composite number with running time only dependent on the size of that number.1

Factoring numbers large enough to break records frequently takes months or years, even with a large number of computers. For instance, RSA-768, the largest number to be factored to date, had 232 decimal digits and was factored over multiple years ending in 2009, using the equivalent of almost 2000 years of computing on a single 2.2 GHz AMD Opteron processor with 2GB RAM.2

It is important to know what size numbers can be factored with current technology, because factoring large numbers is central to cryptographic security schemes such as RSA.3 Much of the specific data we have on progress in factoring is from the RSA Factoring Challenge: a contest funded by RSA Laboratories, offering large cash prizes for factoring various numbers on their list of 54 (the ‘RSA Numbers‘).4 Their numbers are semiprimes (i.e. each has only two prime factors), and each number has between 100 and 617 decimal digits.5

The records collected on this page are for factoring specific large numbers, using algorithms whose performance depends on nothing but the scale of the number (general purpose algorithms). So a record for a specific N-digit number does not imply that that was the first time any N-digit number was factored. However if it is an important record, it strongly suggests that it was difficult to factor arbitrary N-digit numbers at the time, so others are unlikely to have been factored very much earlier, using general purpose algorithms. For a sense of scale, our records here include at least eight numbers that were not the largest ever factored at the time yet appear to have been considered difficult to factor, and many of those were factored five to seven years after the first time a number so large was factored. For numbers that are the first of their size in our records, we expect that they mostly are the first of that size to have been factored, with the exception of early records.6

Once a number of a certain size has been factored, it will still take years before numbers at that scale can be cheaply factored. For instance, while 116 digit numbers had been factored by 1991 (see below), it was an achievement in 1996 to factor a different specific 116 digit number, which had been on a ‘most wanted list’.

If we say a digit record is broken in some year (rather than a record for a particular number), we mean that that is the first time that any number with at least that many digits has been factored using a general purpose factoring algorithm.

Our impression is that length of numbers factored is a measure people were trying to make progress on, so that progress here is the result of relatively consistent effort to make progress, rather than occasional incidental overlap with some other goal.

Most of the research on this page is adapted from Katja Grace’s 2013 report, with substantial revision.

Recent rate of progress

Data sources

These are the sources of data we draw on for factoring records:

- Wikipedia’s table of ‘RSA numbers’, from the RSA factoring challenge (active ’91-’07). Of these 19 have been factored, of 54 total. The table includes numbers of digits, dates, and cash prizes offered. (data)

- Scott Contini’s list of ‘general purpose factoring records’ since 1990’, which includes the nine RSA numbers that set digit records, and three numbers that appear to have set digit records as part of the ‘Cunningham Project‘. This list contains digits, date, solution time, and algorithm used.

- This announcement, that suggests that the 116 digit general purpose factoring record was set in January 1991, contrary to Factorworld and Pomerance.8 We will ignore it, since the dates are too close to matter substantially, and the other two sources agree.

- A 1988 paper discussing recent work and constraints on possibility at that time. It lists four ‘state of the art’ efforts at factorization, among which the largest number factored using a general purpose algorithm (MPQS) has 95 digits.9 It claims that 106 digits had been factored by 1988, which implies that the early RSA challenge numbers were not state of the art. 10 Together these suggest that the work in the paper is responsible for moving the record from 95 to 106 digits, and this matches our impressions from elsewhere though we do not know of a specific claim to this effect.

- This ‘RSA honor roll‘ contains meta-data for the RSA solutions.

- Cryptography and Computational Number Theory (1989), Carl Pomerance and Shafi Goldwasser.11

Excel spreadsheet containing our data for download: Factoring data 2017

Trends

Digits by year

Figure 1 shows how the scale of numbers that could be factored (using general purpose methods) grew over the last half-century (as of 2017). In red are the numbers that broke the record for the largest number of digits, as far as we know.

From it we see that since 1970, the numbers that can be factored have increased from around twenty digits to 232 digits, for an average of about 4.5 digits per year.

After the first record we have in 1988, we know of thirteen more records being set, for an average of one every 1.6 years between 1988 and 2009. Half of these were set the same or the following year as the last record, and the largest gap between records was four years. As of 2017, seven years have passed without further records being set.

The largest amount of progress seen in a single step is the last one—32 additional digits at once, or over five years of progress at the average rate seen since 1988 just prior to that point. The 200 digit record was also around five years of progress.

Hardware inputs

New digit records tend to use more computation, which makes progress in software alone hard to measure. At any point in the past it was in principle possible to factor larger numbers with more hardware. So the records we see are effectively records for what can be done with however much hardware anyone is willing to purchase for the purpose. Which grows from a combination of software improvements, hardware improvements, and increasing wealth among other things. Figure 2 shows how computing used for solutions increased with time.

In the two decades between 1990 and 2010, figure 2 suggests that computing used has increased by about four orders of magnitude. During that time computing available per dollar has probably increased by a factor of ten every four years or so, for about five orders of magnitude. So we are seeing something like digits that can be factored at a fixed expense.

Further research

- Discover how computation used is expected to scale with the number of digits factored, and use that to factor out increased hardware use from this trendline, and so measure non-hardware progress alone.

- This area appears to have seen a small number of new algorithms, among smaller changes in how they are implemented. Check how much the new algorithms affected progress, and similarly for anything else with apparent potential for large impacts (e.g. a move to borrowing other people’s spare computing hardware via the internet, rather than paying for hardware).

- Find records from earlier times.

- Some numbers had large prizes associated with their factoring, and others of similar sizes had none. Examine the relationship between progress and financial incentives in this case.

- The Cunningham Project maintains a vast collection of recorded factorings of numbers, across many scales, along with dates, algorithms used, and people or projects responsible. Gather that data, and use to make similar inferences to the data we have here (see Relevance section below for more on that).

Relevance

We are interested in factoring, because it is an example of an algorithmic problem on which there has been well-documented progress. Such examples should inform our expectations for algorithmic problems in general (including problems in AI), regarding:

- How smooth or jumpy progress tends to be, and related characteristics of its shape.

- How much warning there is of rapid progress.

- How events that are qualitatively considered ‘conceptual insights’ or ‘important progress’ relate to measured performance progress.

- How software progress interacts with hardware (for instance, does a larger step of software progress cause a disproportionate increase in overall software output, because of redistribution of hardware?).

- If performance is improving, how much of that is because of better hardware, and how much is because of better algorithms or other aspects of software.

Assorted sources

- Other pages around e.g. this one, seem to have data for run times etc of other things

- More data on records, probably largely overlapping, including different methods (that I have probably seen elsewhere)

- Announcements such as this one contain much info, many on Scott Contini’s page.

- By “general purpose”, we mean a factoring algorithms whose running time is dependent upon only the size of the number being factored (i.e. not on the size of the prime factors or any particular form of the number). – Scott Contini

- The following effort was involved. We spent half a year on 80 processors on polynomial selection. This was about 3% of the main task, the sieving, which was done on many hundreds of machines and took almost two years. On a single core 2.2 GHz AMD Opteron processor with 2 GB RAM, sieving would have taken about fifteen hundred years. …Our computation required more than 1020 operations. With the equivalent of almost 2000 years of computing on a single core 2.2GHz AMD Opteron, on the order of 267 instructions were carried out. – Factorization of a 768-bit RSA modulus, Kleinjung et al, 2010

- When the numbers are very large, no efficient, non-quantum integer factorization algorithm is known…However, it has not been proven that no efficient algorithm exists. The presumed difficulty of this problem is at the heart of widely used algorithms in cryptography such as RSA. – Integer Factorization, Wikipedia, accessed Feb 10 2017

- ‘The RSA Factoring challenge was an effort, sponsored by RSA Laboratories, to learn about the actual difficulty of factoring large numbers of the type used in RSA keys.’ –RSA Factoring Challenge FAQ

- In mathematics, the RSA numbers are a set of large semiprimes (numbers with exactly two prime factors) that are part of the RSA Factoring Challenge….RSA Laboratories published a number of semiprimes with 100 to 617 decimal digits. Cash prizes of varying size were offered for factorization of some of them. – Wikipedia

- This is because record-breaking numbers appear to be expensive to factor and so unlikely to be done without good reason, or without the attempt being known, and authors on this topic appear to focus on the number of digits that can be factored, so if other larger numbers had been factored earlier, we expect that we would have seen them mentioned. The smallest RSA numbers are an exception, because they appear to have been selected to already be achievable when the contest began, and we do not have much data from before the contest.

- “It is the best of times for the game of factoring large numbers into their prime factors. In 1970 it was barely possible to factor “hard” 20-digit numbers. In 1980, in the heyday of the Brillhart-Morrison continued fraction factoring algorithm, factoring of 50-digit numbers was becoming commonplace. In 1990 my own quadratic sieve factoring algorithm had doubled the length of the numbers that could be factored, the record having 116 digits.” – A Tale of Two Sieves, Carl Pomerance, 1996

- ‘This is a new general purpose factoring record, beating the old 116-digit

record that was set in January 1991, more than two years ago.’ – Factorization of RSA-120, Lenstra, 1993 - Before making our question more precise, let us illustrate its vagueness with four examples which, in the summer of 1988, represented the state of the art in factoring.

(i) In [7, 24] Bob Silverman et al. describe their implementation of the multiple polynomial quadratic sieve algorithm (mpqs) on a network of 24 SUN-3 workstations. Using the idle cycles on these workstations, 90 digit integers have been factored in about six weeks (elapsed time).

(ii) In [21] Herman te Riele et al. describe their implementation of the same algorithm on two different supercomputers. They factored a 92 digit integer using 95 hours of CPU time on a NEC SX-2.

(iii) ‘Red’ Alford and Carl Pomerance implemented mpqs on 100 IBM PC’s; it took them about four months to factor a 95 digit integer.

(iv) In [20] Carl Pomerance et al. propose to build a special purpose mpqs machine ‘which should cost about $20,000 in parts to build and which should be able to factor 100 digit integers in a month.’

– Lenstra et al 1988 - “At the time Of writing this paper we have factored two 93, one 96, one 100, one 102, and 358 one 106 digit number using mpqs, and we m working on a 103 digit number, for all these numbers extensive ecm attempts had failed. “- Lenstra et al 1988